by Augusto Giuffredi

The terms “people” and “statues” are now obsolete. The term “people” was traditionally used to refer to «la parte di una nazione che vive in condizioni economiche, sociali e culturali più modeste» 〈1〉. As for the media, the word “people” has also disappeared from political news because it is now associated with the labor struggles of the last century. Nowadays it is perceived as almost offensive.

The word “statue,” on the other hand, in common parlance refers to a solemn monument, usually placed on a high pedestal in a public place, with the intention of promoting values such as religious faith, love of country, heroism, spirit of sacrifice, and cleverness. From era to era, such values have always provoked critical reactions, whether sarcastic or simply indifferent, expressed through mockery and ironic epithets. Just think of the famous motto “A Laughter Will Bury You All”. It is almost exclusively attributed to anarchist-style political culture, but in fact has its origins in a much more diverse popular reality. The popular custom of renaming statues with alternative, irreverent titles in line with humor and parody can also be traced back to such origins.

This article is the first in a series that will illustrate the relationship between people and statues, as it has been established in the traditions and dialectal idioms of some Italian cities. We will begin with Milan, a city that is one of the most representative in Italy in terms of social stratification, civic culture, relevance and density of its statuary heritage, especially in modern and contemporary times. Here we still remember, for some famous monuments, names born from below, as an alternative to the official title 〈2〉.

Religious subjects

The Madunina, placed on the Duomo’s main spire, is the earliest and most famous example of a popular Milanese appellation (dialect version of the Italian “Madonnina”) that is widely known and used even outside the city. To affectionately call Madunina a 416-centimeter-high statue (iconographically, it is Our Lady of the Assumption) sounds strange, but it is perfectly understandable. Seen from the normal vantage point, the square in front of the Duomo, the statue actually appears very small. The size of the work, conceived in 1774 by the sculptor Giuseppe Perego and realized by the goldsmith Giuseppe Bini through the application of 33 embossed and gilded copper plates on an iron frame, can be appreciated by visiting the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, where a faithful reproduction is exhibited 〈3〉.

The imposing Christ the Redeemer, by unknown author, was made in the 19th century from Ticino gravel and sand mixed with cement. It stands on the terrace of a small building in San Dionigi street, in the Corvetto district. Taken as a whole, and considering the elongated, tapered shape of the building that serves as its base, it resembles the figurehead of a ship. The most common name is El Signurun de Milan (“The Great Lord of Milan”). This is followed by the more prosaic El Cristùn de cement (“The Cement Great Christ”). Both names emphasize the dimensions of the work, which is more than a meter smaller than the Madunina. The figure, out of proportion to its surroundings, blesses pilgrims on their way to the nearby Abbey of Chiaravalle with its right hand raised. But the blessing hand with its three outstretched fingers was also jokingly interpreted as a symbol and reminder of the obligation to pay the quarterly rent. Such a deadline was very much felt in this popular area of the city. Christ’s right hand was lost years ago due to a trivial accident during city maintenance work. Between 2020 and 2022, restoration work led to the reconstruction of the hand and the statue’s original color.

The Monument to Saint Francis by Domenico Trentacoste (1859-1933) was erected in Piazza Risorgimento in 1926, on the occasion of the seventh centenary of the death of the Patron Saint of Italy. The sculptor created the work free of charge, and the casting required fifteen tons of bronze. St. Francis is depicted in the act of blessing. In this impressive ensemble, what immediately aroused the greatest curiosity was the position of the fingers of the two outstretched hands. An attitude that is well summarized in the motto Cinch e tri vott (“Five plus three equals eight”), as if the Saint were playing the morra. Another popular interpretation, more specific, links the position of the Saint’s fingers to the world of workers: Cinch e tri vott, cinq che lavoren e tri che fan nagott (“Five who work and three who do nothing”).

Still on the religious theme, in the courtyard of the Castello Sforzesco stands the Monument to Saint John of Nepomuk, carved in marble by Giovanni Dugnani in 1729, the year of his canonization. Jan Nepomucký (this is the Czech name of the saint) was a canon of the Prague Cathedral and was martyred by drowning in the Vltava River in 1393. He is therefore considered the protector of people in danger of drowning. For this reason, two statues of him were once placed at the Navigli. He is also remembered as the patron of the Austrian Imperial Army, which was stationed in Milan at the time the sculpture was commissioned. The name “Nepomuceno” comes from Nepomuk (Czech Republic), the Saint’s birthplace. It was a difficult name to pronounce at the time, and in the vernacular it became San Giuàn né pü né men (“Saint John, no more and no less”).

Political and historical subjects

The political and historical context has inspired many popular mottos referring to the monuments. It is well known that Napoleon Bonaparte, upon his triumphant arrival in Italy, was seen by a large part of the population as a liberator from tyranny, but such hopes were soon dashed. In the courtyard of Brera, surrounded by the arches that house the marble statues of Milanese celebrities, stands the extraordinary Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker (1810) by Antonio Canova (1757-1822). The figure is depicted as a naked hero, following the Greco-Roman canons of idealization common in the neoclassical period. Such idealization contrasted sharply with the physical figure of the emperor. The nickname given to the bronze statue, Balabiott (“The one who dances naked”), can be interpreted in more than one way, and in less than benevolent meanings. Widespread in the late 1700s, during the organizational phases of the Cispadan Republic, in analogy with the French Sans-culottes, and later adapted to different contexts, it usually indicates an untrustworthy person, a guitto accustomed to changing his attitude and opinions abruptly 〈4〉.

The period leading to unification of Italy and the idea of homeland were also the subject of popular sarcasm. The Monument to Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, is located in the square of the same name, where it was unveiled in 1865. The bronze statue of the politician, by Odoardo Tabacchi (1831-1905), stands on an imposing granite pedestal. Below, an allegorical female figure by Francesco Barzaghi (1839-1892), commissioned by the elder Antonio Tantardini (1829-1879), who at that time could not take on the work, symbolizes Italy. In rainy weather, the statue is covered with water jets that naturally follow predetermined paths. The effect on the statue of Cavour was immediately noticeable, so much so that the monument was ironically nicknamed Cavour che’el pissa (“Cavour urinating in his pants”). This fame was reinforced by the brumisti, the coachmen, who included the monument among the sights to be seen in Milan. To remedy this phenomenon, the monument was turned on its axis after the First World War.

Not far from here, near Piazza Duomo, is the clearing named after Colonel Giuseppe Missori, of the Garibaldian Guards. Inaugurated in 1916, the Monument to Giuseppe Missori is the work of the sculptor Riccardo Ripamonti (1849-1930), who represents the soldier on horseback after the battle, in a vigilant and martial posture. The animal, on the other hand, appears visibly distressed. The contrast between the two figures is striking. This feature struck a chord with the public, and the bronze became known by the nickname Al cavall stracch (“The tired horse”). Today, people who feel exhausted or listless tend to say they are stressed. In those days it was enough to say: te me paret el caval del Missori (“you look like Missori’s horse”). The metal used for the work came from the casting of old cannons and was provided free by the government as the First World War raged. Perhaps for this reason, the sadness of the exhausted horse didn’t go unnoticed.

A decade earlier, in 1906, Giuseppe Missori himself had commissioned the sculptor Ernesto Bazzaro (1859-1937) to create the Monument to Felice Cavallotti, a Garibaldian, journalist, politician and playwright. It was the commissioner who largely dictated the iconography of the work. Had Bazzaro been given more freedom, he would probably have created something less rhetorical and more in keeping with his symbolist temperament. The marble complex is composed of a base in bas-relief depicting a gathering of the people, with the figure of Cavallotti haranguing. At the top, on what looks like a Roman altar, sits a male nude with a Greek helmet and shield, representing Leonidas. The invincible leader of the Spartans appears out of context from the eclectic character referred to here. The monument became known as El Biotton (“The Naked Man”) and was a popular meeting place due to its location in the center of the city. Thus, it became customary to make an appointment by saying Se troeuvom al Biotton (“See you near the Naked Man”). From the beginning, the monument aroused heated controversy, especially in the Catholic press, which considered it a provocation, since Cavallotti was one of the founders of the Parliamentary Left. The very placement of the monument in front of the Ambrosiana building, a library and museum complex highly representative of Christian values, appeared as a hostile act. High level political pressure to move the monument lasted for years. In 1937, thanks to the direct interest of the Duce, Benito Mussolini, the monument was dismantled and placed in a warehouse. It wasn’t until 1952 that it was exhumed and placed in its current location, between Senato street and Marina street.

The Monument to Leonardo da Vinci in Piazza della Scala, a marble group in which the great renaissance artist stands out surrounded by his four best Milanese pupils, is one of the most representative images of the city. It is the work of Pietro Magni (1816-1877), one of the best interpreters of 19th century Italian sculpture. Since its inauguration in 1872, the work has been the subject of criticism, mainly for its excessively metered compositional geometry, with the four young men strictly subordinate to the master. Criticism well summed up in the motto attributed to the journalist and storyteller Giuseppe Rovani: Un liter in quater (“One liter and four glasses”). For the young artists and intellectuals of the milanese Scapigliatura, the monument appeared as a rhetorical self-celebration of a city in the midst of his cultural and economic evolution.

With the Monument to the Five Days of Milan, conceived around 1880 and inaugurated in 1895, Giuseppe Grandi (1843-1894) created an extremely dynamic structure, in vivid contrast to the regularity of the Monument to Leonardo da Vinci. It took the sculptor thirteen years to complete the work, and he died before it was inaugurated. In order to best study the allegorical figure of the lion, Grandi had to obtain a live lion, and the anecdote was immediately circulated. According to the funniest version, the sculptor had purchased from a circus a lion named Borleo, known for his peaceful temperament, ill-suited to symbolize rebellion and ferocity. It is said that to stimulate him, the sculptor threw balls of clay and plaster into the lion’s cage, which ingested them and developed an intestinal blockage. To cure the animal, it had to be given an enema. This had the desired effect, and the lion uttered the convulsive roar immortalized in bronze. The anecdote spread, and the bronze lion in Piazza Cinque Giornate became known as El poer Borleo (“The Poor Borleo”).

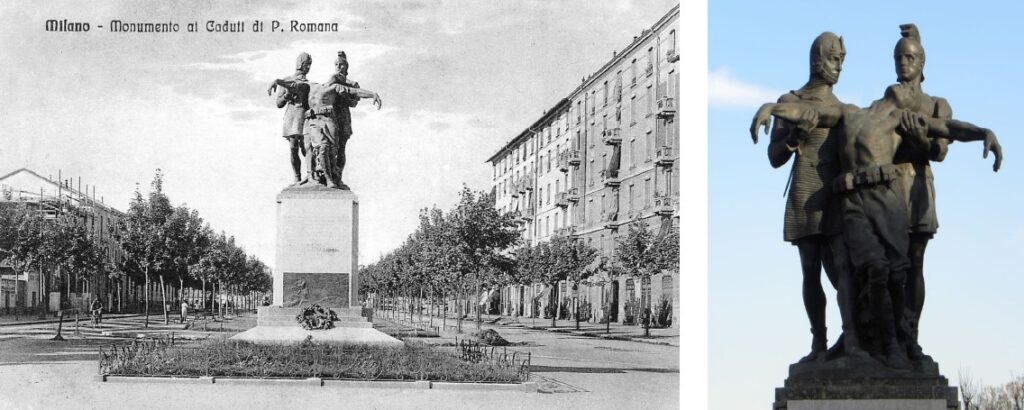

First World War evokes human sacrifices that are as immense as they are often completely unnecessary. When subjects of such magnitude are represented in a rhetorical, iconographically ambiguous way, it is normal that they evoke irony and sarcasm. This is the case of the War Memorial at Porta Romana, inaugurated in 1923 to commemorate the victims of the first aerial bombardment of Milan. It stands in the area where the bombs dropped by Austrian planes fell on February 14, 1916. The sculptor Enrico Saroldi (1878-1954) conceived a group of three figures made up of a Roman soldier and a medieval soldier of the Lombard League, who are about to carry the body of a victim. The choice of the two soldiers is explained by the fact that centuries ago both the Roman army and the medieval communes had to deal with the Germanic enemy. However, the juxtaposition is far from clear to the ordinary viewer. No wonder the Milanese nicknamed the opera I tri ciucc (“The Three Drunks”). Indeed, it evokes the scene in which three friends, two of them apparently tipsy and dressed in carnival costumes, hold up another in an ethyl coma in order to take him home.

Erotic Subjects

The repertoire could not lack a section dedicated to carnality and eroticism. The Fountain of the Tritons, designed by the architect Alessandro Minali (1888-1960) and built in 1928 in Andegari Street in pseudo-baroque style, has two allegorical figures sculpted in marble by Salvatore Saponaro (1888-1970). The Allegory of Savings holds a money box whose shape resembles a breast, so much so that it is known as La dona di trè Tètt (“The Woman with Three Breasts”).

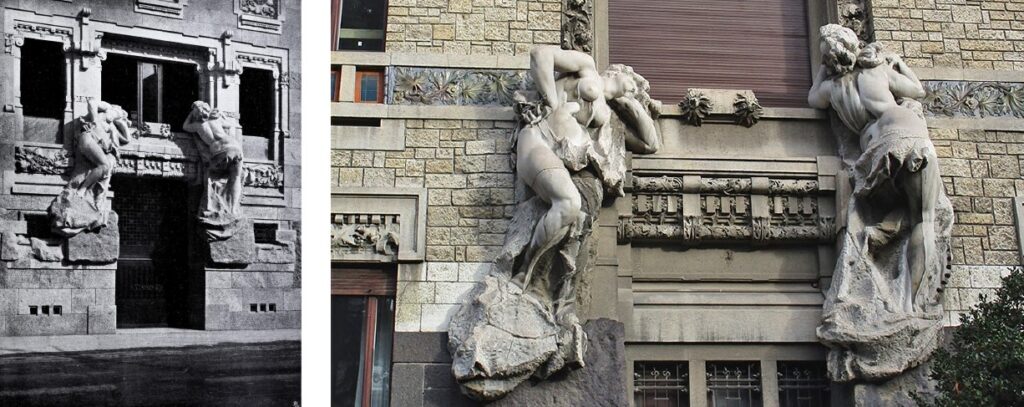

In 1901, architect Giuseppe Sommaruga (1867-1917) designed one of the most original Art Nouveau facades in Milan for the Castiglioni Palace in Corso Venezia. It featured two allegorical marble figures, Industry and Peace, created by the sculptor Ernesto Bazzaro (1859-1937). The seductiveness of the female nudes and their provocative poses earned the building a nickname that soon made it an object of ridicule and criticism: La cà di ciapp (“The House of Buttocks”). As a result of the scandal, the property had the statues dismantled and Sommaruga moved them to another, less prominent building, Villa Faccanoni, in Buonarroti Street.

When the Canals (“Navigli”) that encircled the historic center of Milan was still in operation, a cast-iron bridge stood near what is now Pietro Mascagni Street. Built in 1842 to the design of engineer Francesco Tettamanzi, it was the city’s first iron bridge. The structure was cast in iron at Ferriere Rubini-Falck-Scalini & C. in Dongo and decorated with four mermaid figures, also in iron, based on a plaster model by Benedetto Cacciatori (1794-1871). In 1930, following the silting up of the Canals, the bridge was dismantled and later reassembled in Sempione Park, where it still stands today. From the beginning it was renamed in two ways, both alluding to the four fish women: Il pont di sorèi Ghisini (“The Bridge of the Ghisini Sisters”, where the surname Ghisini comes from the cast iron – “ghisa” in italian – of which the statues are made) and Il pont di sorèi di ciapp, (“The Bridge of the Sisters with the Buttocks”), referring to the fact that the buttocks of the four statues were perfectly shaped. The bridge became a destination for romantic rendezvous, and it was believed that touching the mermaids’ breasts before a rendezvous would bring good luck.

Older occurrences

Popular inscriptions also survive on older Milanese statues. An example is the façade of the palace that the sculptor Leone Leoni built for himself around 1565. On the ground floor there are eight telamons, referring to as many known barbarian tribes in the Roman Empire, carved in marble by Antonio Abondio. Because of their size, they were immediately renamed Omenoni (“Big Men”). Cà di omenoni (“House of the Big Men”) was the name with which the palace was immediately identified. The street was given the same name, which became part of the city’s toponymy.

This review concludes with El Sior Carera (“Mr. Carera”) or L’omm de preja (“the man of stone”), a Milanese version of Rome’s Pasquino. This is a Roman statue located under a portico on Via Vittorio Emanuele II in the heart of Milan. Engraved at the base of the statue is a Latin phrase with a moralizing tone that reads: Carere debet omni vitio qui in alterem dicere paratus est 〈5〉. The first word in the Latin quote, the verb carere, is the cue for the character’s dialect name: Sior Carera, to be exact. Anonymous messages of complaints or invectives were pinned to his shoulders, just as in Rome with the other ancient statue fragment renamed Pasquino. It would be a good idea to restore the custom of these postings, instead of the spray-painted exterior walls.

〈1〉 «The part of a nation living in more modest economic, social, and cultural conditions». See under "Popolo" in the Dizionario dell'italiano Treccani, online version: https://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/popolo/ 〈2〉 General works that can be consulted on the subject: G. Mongeri, L'arte in Milano. Note per servire di guida nella città, Società Cooperativa fra Tipografi, Milan 1872; A. Stella, Pittura e scultura in Piemonte, 1842-1891, Paravia, Turin 1892; VV.AA., Guida d'Italia. Milano, Touring Club Italiano, Milan 2015; F. Mezzotera, Milano curiosa. Tutto ciò che c'è da scoprire in città, Magenes, Milan 2024. Among the best sites: www.milanocittastato.it 〈3〉 On the Madonnina del Duomo: M. Cordani (ed., with photographs by M. De Biasi), La Madonnina di Milano, CELIP, Milan 2003. 〈4〉 On the Napoleonic imagery in Milan: F. Mazzocca, Napoleone e Milano tra realtà e mito. L'immagine di Napoleone da liberatore a imperatore, Skira, Milan 2021. 〈5〉 «He must be without vice who is about to criticize another». The phrase comes from an oration attributed to Cicero against Gaius Sallustius Crispus. See C. Lanza (ed.), Declamazione contro C. Crispo Sallustio attribuita a M. Tullio Cicerone, in Le orazioni di M.T. Cicerone, Paravicini, Napoli 1870, vol. III, p. 268. Homepage: View of the courtyard of Palazzo Brera with, in the center, Canova's bronze depicting Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker (Giovanni Dall'Orto/Wikimedia). Below: the Fountain of the Tritons; detail with the Allegory of Savings.