by Simone Martinotta

Hélio Oiticica. Biographical notes

European modernism, rooted in the historical avant-gardes, programmatically marginalised craft and decorative practices. The artistic currents of the Old Continent shied away from ornamental risk, and it was not until the end of the 20th century that there was a rediscovery, albeit partial, of the resources of ornament in painting, sculpture and architecture.

In the peripheries of the Western world, however, modernist taboos had less impact, not so much as to completely erase the memory of the indigenous traditions that had prevailed there until recently. The artists who worked in these contexts were thus able to play a pioneering role, even though they were trained in European-style academic culture. With a certain anticipation due to their frontier position, they were able to rediscover, along with the fascination of the cultures born of the encounter between indigenous peoples and European colonisers, that visual heritage which, in highly civilised Europe, seemed more like an archaic residue, a folkloric curiosity unsuited to a modern, organised and efficient communicative context 〈1〉.

One example is one of the most important South American artists of the second half of the 20th century, first in the field of abstraction, then in the field of conceptual performance: the Brazilian Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980) 〈2〉. Born into a bourgeois family from Rio de Janeiro – hence the name “carioca” for the city’s long-time inhabitants – the young Hélio was brought up in a vibrant and cosmopolitan cultural environment. His father, José Oiticica, a poet, playwright, philologist and anarchist, was one of the protagonists of the Brazilian cultural and political scene between the two world wars. Between 1947 and 1954, José lived with his family in the United States, where Hélio would return many years later, thanks to a Guggenheim Fellowship that allowed him to live and work in New York between 1971 and 1977.

Against the wishes of his father, who wanted him to study engineering, Hélio came into contact with the sources of international abstract art: from Malevič to Klee to Mondrian. It was the work of the latter, who died in New York in 1944 and was also well known in America, that had the greatest influence on the young artist’s beginnings, who soon realised the limitations of two-dimensional painting and began to experiment with mixed forms articulated in space.

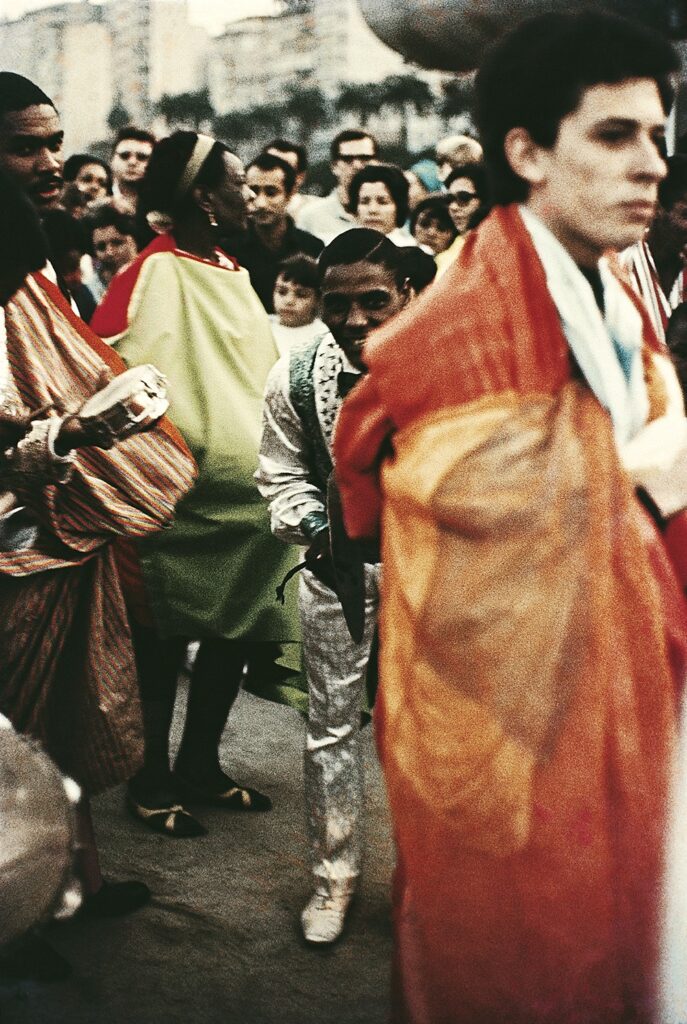

The decisive turning point in Oiticica’s artistic career occurred in 1964, coinciding with a stay in the Mangueira district, in the heart of Rio’s urban agglomeration, where he attended the local samba school, one of the most important in Brazil. It was during this experience that Hélio began to conceive works of a participatory, dynamic, joyfully political nature, initiating the Parangolé series (1964-79). His work was nourished by the customs of the favelas – the slums where the poorest and most marginalised live – and in particular by the social and organisational role that dance, costumes, carnival and floats played within the community.

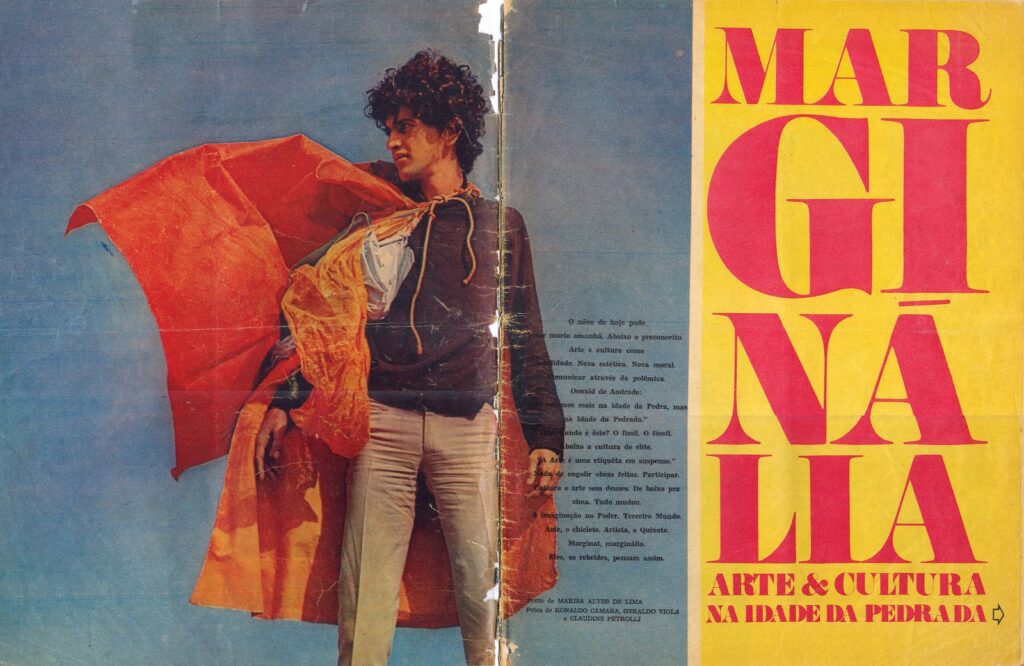

Oiticica’s ability to draw on these mestizo traditions, and to reinterpret them in a very free creative way, linked his work to what was happening in music, theatre, poetry and film in those years, with the Tropicalist movement. In the background, the military dictatorship that ruled the country from April 1964 until the 1970s, before gradually returning to democracy in the 1980s, imposed silence and exile on its opponents 〈3〉.

In 1969, as an artist-in-residence at Sussex University in Brighton, Oiticica moved from Rio to London, where he exhibited at the Whitechapel Gallery. The following year, he was one of the artists included in Information, a major exhibition at the MoMA in New York that took stock of research in the conceptual field. 〈4〉. His stay in New York brought him international fame and a new vision of Brazilian popular culture. Not only the visual arts, but also journalism and photojournalism owe much to his sociological and anthropological perspective.

He returned to Brazil where he died of a cerebral haemorrhage at the age of forty-two. Among the initiatives still linked to his intellectual legacy are “Parangolé. A journal about the urbanised planet”, a review of design, architecture and urbanism, which is still in its first issue, to be published in 2021 〈5〉.

The neo-avant-garde beginnings

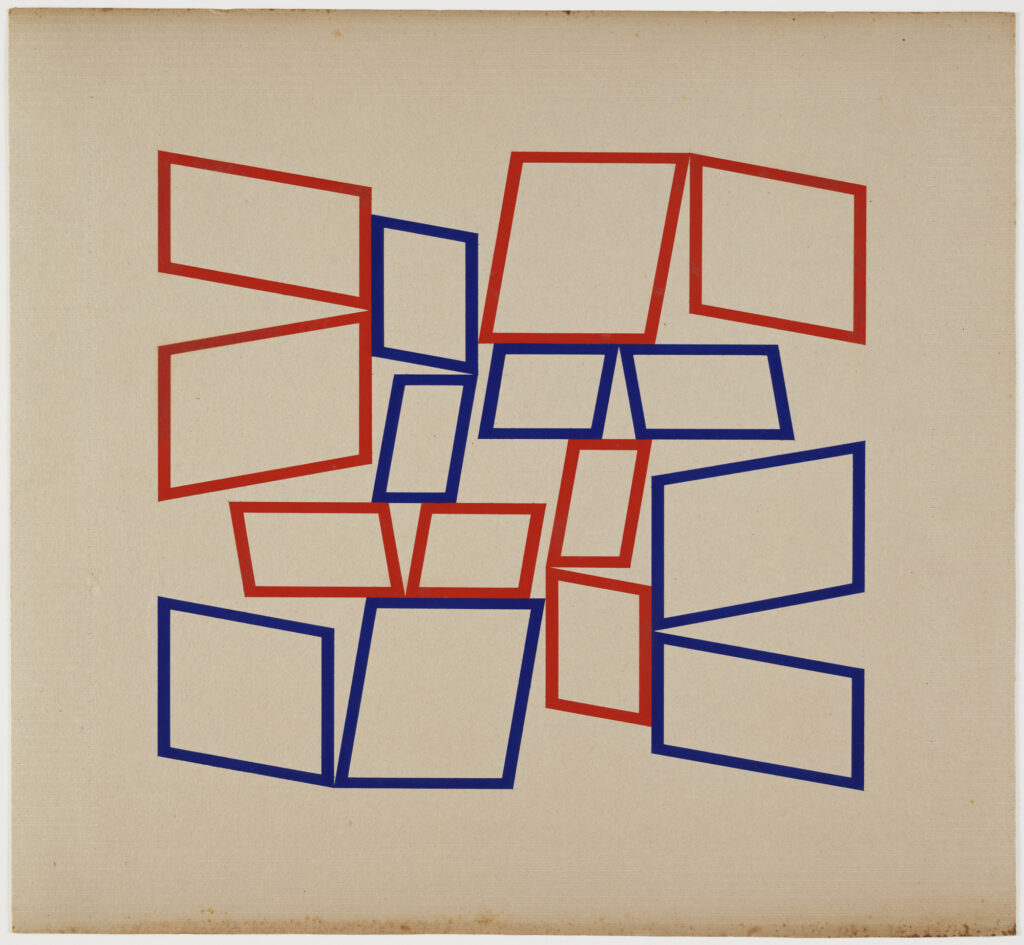

In the art of the 1950s, concretism and the neoplastic legacy gave rise to a rich pictorial flowering. It was also used by the Brazilian avant-garde in Rio, made up of artists of European origin and culture, in which the young Oiticica was formed 〈6〉. In 1954-55 he joined the Grupo Frente led by Ivan Serpa, the cradle of Brazilian Concretism. In this early phase of his painting, Oiticica produced works characterised by the use of regular geometric forms, with a chromatic palette that was initially reduced and then gradually expanded to include less conventional tones. The artist’s interest in rhythmic structures, with a certain degree of modularity and recursiveness, is evident in these early attempts.

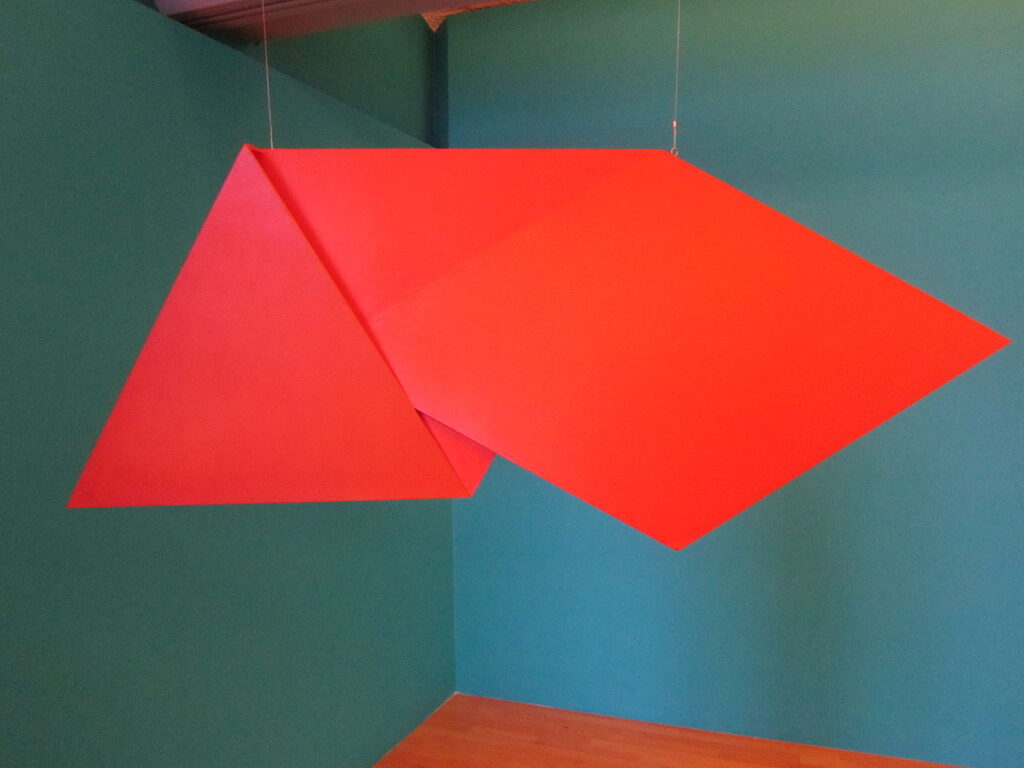

In 1959, Oiticica (along with Amilcar De Castro, Franz Weissmann, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape and others) became part of Neoconcretism, a new group that emerged in Rio in response to stimuli from the post-informal, pop and neo-dada fronts. In this context, pictorial two-dimensionality no longer seemed an insurmountable barrier, and three-dimensional environmental operations were born, in which detached contemplation gave way to direct physical involvement. The most important works of this period are the Invencoes series (1959), square panels of wood, thirty centimetres on each side, made with the ultimate aim of setting the canon of painting to zero with colour, while remaining in close contact with it. They represent an important stage in the Brazilian artist’s work: the first in a process of transition that would lead him to a typology of installation in which the viewer himself is an essential element.

In 1961, the Neo-Concretist group disbanded, undermined by internal disagreements and the ongoing ideological clashes in the country. Lygia Clark and Oiticica himself responded by moving in the direction of what would later be called Conceptual Art. Oiticica, however, never embraced the tendency towards dematerialisation and tautology inherent in Conceptual Art. The relationship between body and space was central to his interests and led him to develop a versatile, light, ephemeral type of sculptural object. A clear example of this is the Bólides series (1963-79), which consists of stacked wooden supports around which the viewer stands to explore the spatial dimension in 360 degrees.

The transition to an installation on an environmental scale, physically traversable, is well illustrated some time later by Tropicalia (1967), an installation (penetrável, according to the Portuguese-Brazilian neologism coined by the artist) made with poor materials such as raw wood, plastic and plant elements, aimed at recreating the sense of temporality, of urban reality in perpetual evolution, typical of the slum.

Parangolé

The Brazilian artist’s work on concretely humanised and lived space culminated in the development, from 1964, of several series of portable works called Parangolés. The term was so successful that many years later it was used to baptize a famous musical group from Salvador de Bahia. Few remember that it was Oiticica himself, with his talent as a tightrope walker of words, who circulated it in the identity meaning still in use today 〈7〉.

In the multiethnic reality of Mangueira, the artist came into direct contact with the customs and traditions of the lowest rung of the Brazilian social pyramid. Attending the samba school in the neighbourhood, he began to create imaginative costumes that resembled folding banners, made of very poor materials, but composed in an effective and harmonious way to sublimate a common stage object into an emblem of the state of invisibility of a significant part of the population. Shaken by the movements of the dance, the costumes resolved themselves into mobile sculptures, indulging in that playful, dionysian vein, projected in bodily action, that was increasingly asserting itself in Oiticica’s production. Not infrequently, they were accompanied by writings, both poetic and political, placed in plain view during the performance. Parangolé ‘s appearance at the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro, during the exhibition Opinião 65 (1965), caused a scandal. The collective performance in which it was used had to take place outside the museum.

It was thanks to the communicative power of an anomalous object like the Parangolé that themes of exclusion and marginality began to arouse an interest that was not simply exotic or folkloric. With Oiticica (who, incidentally, made no secret of his own homosexuality, foreshadowing a mode of communication that was to become widespread much later), artistic practice became a vehicle for the dissemination of individual and collective instances of redemption, translated into visually pregnant, anti-intellectualist emblems, far removed from the subtle balancing acts of the neo-avant-gardes. His work contributed to a profound rethinking of the image of Brazil and its inhabitants, challenging the picturesque tourist clichés of the time.

On closer inspection, the Parangolés are characterised by the use of inferior fabrics, plastic fibres and recycled materials in general, which are characteristic of the favela economy. With a precise choice of field, the artist wanted to privilege the resources normally found in Rio’s slums, subjecting them to a treatment that would give them an unmistakable symbolic value without mystifying their reality of origin.

Ideals that are widespread today, such as those of reappropriation and identity, began to emerge powerfully in Oiticica’s conception. He used discarded materials that corresponded to a dramatic social cross section of Brazil to reuse them according to a utopian logic of sharing, responding to an idea of fair exchange (as we would say today) rather than financial economy. The theoretical premise of the operation was that the population of the neighbourhood could fully recognise themselves in the final product of Oiticica’s work, precisely because it drew on their daily experiences, highlighted their cultural dignity and coherently developed its methodological indications.

There was a clear synergy between the artist and the Mangueira neighbourhood. The rich festive choreographies, in which the inhabitants of the neighbourhood collaborated en masse, injected a wealth of unusual shapes and colours, almost a new genetic code, into Oiticica’s production. Soon Parangolé became part of the costumes of samba dancers, the dance that, thanks to the local associations and schools that are still its most recognisable expression, best embodies the characteristics of Brazilian culture as it was shaped by the encounter between Europeans, indigenous cultures and African traditions imported with the slave trade.

The success of Parangolé led the artist to create a series of garments characterised by easily recognisable compositional and chromatic variations, as in a heraldic language extolling pride in one’s roots and instances of redemption. Seen today, the recovery of the content of decorum (i.e. human and cultural dignity) associated with clothing, not codified in Western, bourgeois terms, gives Oiticica’s work a great impetus. The centrality of the European way of conceiving the work of art and its social, intellectual and philosophical prestige is questioned.

From this perspective, the role of those who, although not artists, enter into a symbiosis with the work should also be reconsidered: no longer passive observers, but users and participants, helping to make the dress or wearing it to dance. Almost a prologue, in the very difficult context of Mangueira, to the participatory art experiences that were taking shape both in Europe and the United States.

Parangolé, yesterday and today

The titles that the Carioca artist gave to his works soon became recurring slogans in the protests of Brazilian citizens against the ruling military junta. In their vitalism, in their deliberate appeal to a substantial decency as opposed to an exclusively formal one imposed from above, Oiticica’s actions represented a glimmer of light in the oppressive darkness of the dictatorship. Terms such as Tropicalia and Parangolé served as a guide for the inhabitants of the favelas, who used them as a banner in opposition to the elites from whom the artist himself had distanced himself. While 1988 was the year of the country’s official return to democracy, the slogans formulated by Oiticica survived the end of the regime to become symbols of Brazilian culture around the world.

In an increasingly globalised situation such as that of the new millennium, one of the many design proposals is the idea of Parangolé City, developed by the Venezuelan architecture firm Urban Think-Tank (Alfredo Brillembourg and Hubert Klumpner), which appeals to the ideal of fusion between the body, art and dance advocated by Oiticica. The symbiosis between man and the metropolis is at the heart of the proposal, tested in the reality of the metropolis of São Paulo, where disproportionate urban growth has challenged the transport system and led to the proliferation of slums 〈8〉.

Oiticica’s legacy is, of course, most evident in music. There have been many groups that have paid homage to Parangolé with their own compositions, extolling his communal values. Born in 1997 in the bairro Federação in Salvador de Bahia, the group Parangolé, led by Léo Santana, has achieved worldwide fame with songs such as Swing do Cavaco, Timanamanô and Colé Véio.

Experiences paying tribute to Oiticica and his Parangolé have found fertile ground in the visual and performing arts of this early 21st century. On the one hand, the great exhibitions that reconstruct the Brazilian artist’s creative itinerary, philologically analysing his materials, tools and processes, do an indispensable and meritorious job, but they cannot fully restore the eternal vitality and movement to which Oiticica wished to transmit his message. One thinks, to give a measure of the phenomenon, of the Parangolé proposed in 2019-20 at the MoMA in New York, where the artefact, exhibited in the static mode proper to a painting or a tapestry, figured as a mute witness, now inert, of an affair in which dynamism, movement in space and time, had been the indispensable prerequisites 〈9〉.

On the other hand, Oiticica’s popularity is such that it allows his inventions to be used posthumously as part of a repertoire, similar to what happens with the covers of rock stars. A recent Italian example is the carnival organised for the past 20 years by the self-governing social centre “Spartaco” in the Quadraro district of Rome. In this context, in 2016, the ATI collective gave substance to a performance that took up precisely the methodological directions offered many years earlier by the Brazilian artist 〈10〉.

Perhaps the most important fact to reflect on is this: a line of continuity between the world of Oiticica and that of today is not only perceptible, but often evident. As the memory of the Brazilian artist recedes with time, the cities that in different ways remember and commemorate him, in terms of ethnic composition and processes of gentrification and social disarticulation, increasingly resemble the Rio de Janeiro in which he passionately lived and studied.

〈1〉 In this regard, the case of the New Zealand artist Gordon Walters is one of the topics already covered on FD. See E.M. Davoli, Gordon Walters: i Koru Paintings, 3 February 2021, www.faredecorazione.it/?p=13791 〈2〉 About Oiticica's life and work, see: a) the catalogues of the most recent posthumous exhibitions: M.C. Ramirez (ed.), Hélio Oiticica, The Body of Colour, Houston, Museum of Fine Arts, 10 December 2006-1 April 2007, London, Tate Modern, 6 June-23 September 2007; L. Zelevansky et al. (ed.), Hélio Oiticica: To Organise Delirium, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Museum, 1 October 2016-2 January 2017, New York, Whitney Museum, 14 July-1 October 2017; A. Pedrosa (ed.), Hèlio Oiticica. Dance in my Experience, Sao Paulo, MASP, October 13-November 22, 2020; C. Oiticica et al. (ed.), Hèlio Oiticica, New York, Lisson Gallery, 28 October 2020-23 January 2021; b) a monograph: I.V. Small, Hélio Oiticica. Folding the Frame, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago-London 2016; c) several editions of Oiticica's theoretical texts and interviews: H. Oiticica, Encontros, Azougue, Rio de Janeiro 2009; H. Oiticica, Museu é o mundo, Azougue, Rio de Janeiro 2012; H. Oiticica, The Great Labyrinth, Hatje Cantz Verlag, Ostfildern, 2014; H. Oiticica, Experimentar o experimental, Azougue, Rio de Janeiro 2023; d) Oiticica's poetic texts: H. Oiticica, Secret Poetics, Soberscove Press/Winter Editions, Chicago 2023; e) two dissertations available online: M. Asbury, Hélio Oiticica: Politics and Ambivalence in 20th Century Brazilian Art, PhD Thesis, London, University of the Arts, 2003; E. Matteucci, Il potere politico del colore. Arte e partecipazione nel lavoro di Hélio Oiticica (1937-1980), Venice, Ca' Foscari University, 2021. 〈3〉 As with other defining terms in Brazilian culture, Oiticica's contribution to the definition of 'Tropicalism' is crucial. It was his installation Tropicália (1967) that inspired the musician Caetano Veloso to title his 1968 LP of the same name, hence the definition of 'tropicalista movement' to refer to the young libertarian Brazilian culture that was hostile to the military junta that ruled the country from 1 April 1964 to 15 March 1985. 〈4〉 See K. McShine (ed.), Information, exhibition catalogue, New York, MoMA, 2 July-20 September 1970. 〈5〉 The website: www.parangoleweb.com 〈6〉 About history of the artistic avant-garde in Central and South America in the 20th century: M.C. Ramirez, H. Olea, Inverted Utopias. Avant-Garde in Latin America, Yale University Press, New Haven 2004. 〈7〉 About Hélio Oiticica's Parangolé : D. Romero Keith, Hélio Oiticica. Parangolé, Mousse, Milan 2023. When Oiticica began to use it, "parangolé" was a slang expression used in Rio de Janeiro with the meaning of "sudden agitation", "excitement", "joy", "surprise". 〈8〉 About the work of the firm headed by Brillenbourg and Klumpner, see the website www.uttdesign.com 〈9〉 The Parangolé (an original dated 1965, reconstructed in 1992, part of the Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift) appeared in the exhibition Sur Moderno. Journeys of Abstraction-The Patricia Phelps de Cisneros Gift, edited by I. Katzenstein, New York, MoMA, October 21, 2019-March 12, 2020. 〈10〉 See the ATI collective's website at www.atisuffix.net/parangole Homepage; Hélio Oiticica wearing a Parangolé during a performance in the 1960s, frame from Ivan Cardoso's documentary "HO" (1979). Below; Hélio Oiticica, Relevo espacial, 1960, acrylic on plywood, 85 x 88 x 105 cm, Waltham/Boston, Massachusetts, Brandeis University, The Rose Collection.