by Enrico Maria Davoli

The bibliography on sacred art and architecture in the modern age is vast and growing, thanks to the impetus given by the Second Vatican Council sixty years ago. The debate is also of interest to the uninitiated, as shown by the controversies that arise whenever the liturgical adaptation of a place of worship is undertaken, be it an illustrious monument or a minor reality known only to regular visitors. The proceedings of the conference Architettura e teologia nella costruzione di chiese, held at the Faculty of Theology in Lugano on 29 April 2002, provide an example of some very useful intellectual and professional positions for assessing the current state of affairs. Let us briefly review them.

Arturo Cattaneo, professor of Canon Law, in his opening speech, summarised the essential requirements to which a Church must respond, keeping an equidistant distance from the very heterogeneous proposals on the table today.

Artist and art historian Rodolfo Papa takes stock of the marriage between architecture and the figurative arts in the Christian tradition, diagnosing a critical issue that, while ignored by the contemporary mainstream of the self-sufficient, self-signifying “author church”, is nevertheless a sore point. That is, an architecture that is incapable of accommodating things and visions “other” than those of the designer will be a fortiori incapable of accommodating the divine. Sacred art is indispensable to sacred architecture; the latter cannot exist without the former.

As an architectural historian, Andrea Longhi seems to be in continuity with the previous position. However, his appeal to the church as a collective creation, the result of the interaction of many historical, cultural and social components, evades a fundamental question: how is it that contemporary architectural design, in a type of building that seeks more than any other to embody instances of universality and permanence, so often resolves itself into a soliloquy?

As a historian of christian art, Ralf van Bühren draws up a synthesis of sacred architecture in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, but glosses over the period before the Second Vatican Council, as if this event had automatically rendered all that had gone before invalid. This is a serious underestimation, if it is true that history does not die with those who make it; on the contrary, it lives on in the lessons that posterity can draw from it.

Finally, the architects Paolo Zermani and Mario Botta evoke, in exquisitely subjective terms (as is the status of today’s practitioner, free from constraints other than those of personal poetics), the salient stages of their careers in the sphere of the sacred.

What lessons can be drawn from such a diverse landscape? We will try to formulate some here, not necessarily in line with the findings of the Lugano conference. First, it is now clear that the experimentalist and neo-avant-garde strand of the second half of the twentieth century has run its course. This is not because its most precious pearls have lost their value, but because, in the incessant becoming of which they themselves are a part, they fail (as they have never succeeded) to exert that normative, guiding influence which has always been the province of the masterpieces of every age. Let us take the best known and most admired of these gems: the Chapelle de Ronchamp, which has also been mentioned several times in these proceedings. No one is denying Le Corbusier’s building the licence of a masterpiece, let us be clear. The problem is different: like all works, however great, born from the radical deconstruction of a model – be it a dolmen, a temple, a basilica – Ronchamp is inimitable in the literal, etymological sense. That is to say, it does not belong to a single architectural type, but alludes to several, without identifying itself with any of them, and it cannot be the progenitor of a solution that would be dispensable in a context different from its origin: more prosaic, less artistically guarded, or simply not illuminated by that King Midas touch that is specific to its author. In short, an exception, however great, cannot become the rule. On the contrary, the more they try to imitate the inimitable, to approach the unattainable, the more paradoxical they become and the more they become an end in themselves. The contemporary history of ecclesiastical architecture, in the hands of a few great architects and their epigones, is just that: a few jewels and a myriad of trinkets that try in vain to vibrate with that light, to arouse that excitement. What is missing is an average, recognisable and sustainable level.

Where, then, should we look for examples of decorum – to use a key word from this magazine – that are compatible with the standards of the 2000s? In our opinion, in another 20th century: that is, in the first half of the 20th century, which was still alive and productive in the 1950s and which is now dismissed as a grey area, full of ambiguities to which it pays not to pay attention. Among the greats, the case of Auguste Perret (1874-1954) is instructive: eclipsed in popularity, fame and ideological expendability by his student Le Corbusier, he is usually dismissed as the last link in a chain that has now become too long. But it is precisely his attachment to archetypal forms, starting with the basilica, that gave him great freedom and expressive authority, that made his spaces concrete and inhabitable (even by the works of other artists), even with the revival of the theory of architectural orders.

But let us stay in Italy. Here, the first half of the twentieth century is an inexhaustible and little-known mine of solutions, exploring the whole scholarly range of the sacred in architecture. The construction of new towns and villages, which culminated during the Fascist regime (with all the historiographical totems and taboos that arose on all sides from the difficulty of confronting the artistic culture of the Ventennio), offers rich deposits of pragmatic, anti-rhetorical modernity, full of the priceless luxuries that are the truthful use of materials, the ornamental use of beams and bricks, the images embedded in the walls by mosaic, stained glass, majolica and fresco. The history of these decades is full of exciting experiences: rich even in the cheapness of materials, highly original even in the respect of archetypes.

If it is true, as is often said, that beauty lies in the details, then archetypal forms, interpreted with the necessary dose of literalness, are an unparalleled test for church architecture. They exalt the talent of those who know how to vary the theme and enhance its nuances; they dismantle egocentrism, narcissism and personalism; they promote the civic, urban values of which they are the materialisation. On the other hand, spectacular but extemporaneous inventions are functional for the immediate recognition of the work and the author, for the focus (especially in photographs intended for specialist magazines and the media) on this or that salient feature. The salient feature may be to make the symbol of the cross (reduced to an aniconic pattern) appear where one would least expect it, or to move architectural forms and connections (domes, apses) as in a gigantic origami, moved by an inextricable logic. The result of these exercises is to turn the symbol into an esoteric apparition, the gymnastics of the forms into an exhibited culturism, thwarting the meaning of religious experience.

It seems that at present a substantial agnosticism pleases both the planners, who are free to indulge in mannerist mysticism, and the religious patrons, who, if they were less neutral, would immediately be accused of being illiberal, autocratic, neo-absolutist, restorative, and so on. Perhaps the impasse on both sides could begin to unravel if some questions were asked. For example, if – as Zermani does, quoting the medievalist Jacques Le Goff in the title of his lecture – the present age is called ‘the age of the merchants’, why not apply the same interpretive measure to other principles of architecture? Materialism for the sake of materialism: how is it that a large retail chain, a multinational DIY company or a global fast-food brand can give their designers extremely precise instructions and that their sites are instantly recognisable and homogeneous? Why is it that Islamic finance is so liberal when it comes to commissioning our architects to design the headquarters of museums, boutiques and banks, but so inflexible about every detail when it comes to building mosques?

Some will say: those who work only for profit, those who do not even know what the separation of religious and secular power is. But then one realises that the great world of commerce, of the West and the East, is hoarding stylistic features finely tuned in the sphere of church architecture, thus confirming the sacredness and inviolability of its universal mission. There is no exhibition pavilion, supermarket or private clinic that does not display the metal version of the top-branching column tree that the whole world admires in the stone version of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia. And that is just one example. Might it not be time for the Church to take an active interest again in the images to which it has long given its heart and soul? This too is a claim (materialistically speaking) to be made.

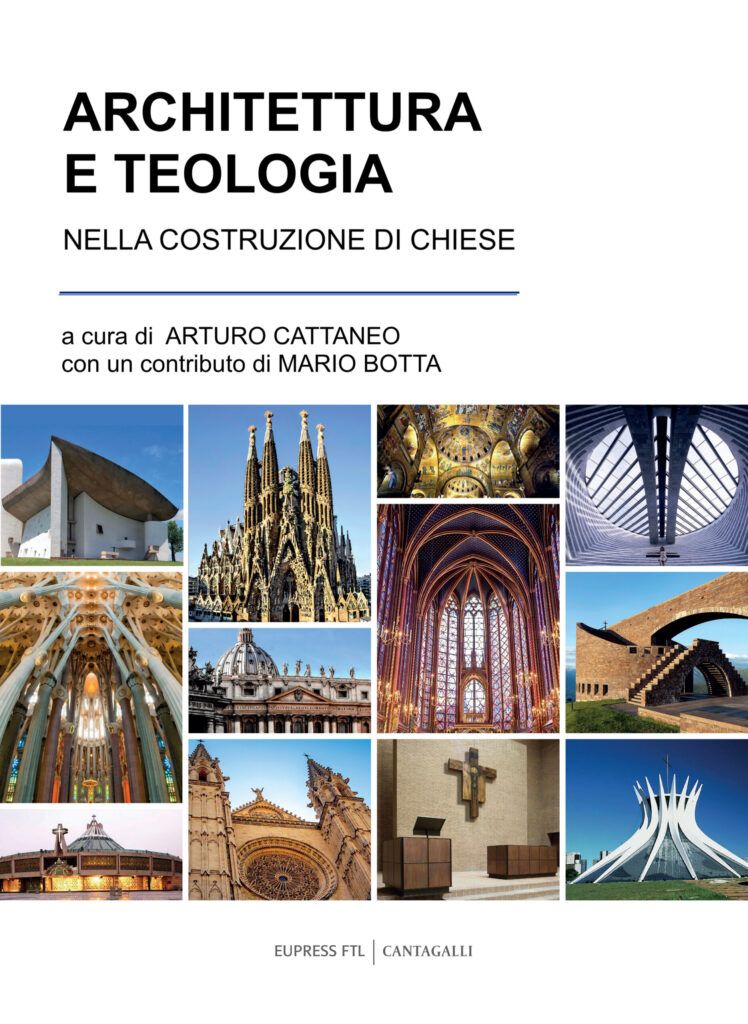

The book: Carlo Cattaneo (ed.), Architettura e teologia nella costruzione di chiese, Eupress-Cantagalli, Lugano-Siena 2023, pp. 170, euro 22.

Homepage; a view of the central square of Arsia (Raša), Croatia, with the church of St. Barbara (architect Gustavo Pulitzer Finali, 1936-37, photo credits Paolo Mazzo). Below; the book cover.