by Sara Palestra

Origins and applications

The culture of the United States has an original and unique testimony in quilting, both in terms of sartorial techniques and fabrics used, as well as in terms of socio-historical implications, compositional modes, and subjects depicted.

Already loved and imitated in England, quilts of indian origin were instrumental in bringing the technique to the New World. The popularity of quilting in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries makes it reasonable to assume that its arrival in America dates back to the very first landing of english settlers; the Puritans who arrived aboard the Mayflower in 1620. It can be argued that quilting, as it is understood today, is a distinctly american invention, but with european, middle eastern and indian influences 〈1〉.

American women have been quilting since colonial times. This can be explained by the specific way in which the process was carried out. Unlike other sewing activities, quilting allowed several people to work on the same quilt at the same time. Teamwork was doubly rewarding. First, because it sped up the completion time; second, because it fostered the exchange of ideas and knowledge, primarily related to the family environment, but also extending to religious, social, and political issues.

In other words, working on a quilt could amount to working out, in cipher form, a heritage of sensibilities and ideas that had matured collectively, on a par with what happened (among white communities, but also among slaves of african descent and among native americans) with other group activities, such as choral singing. Given that the main function remained that of bedspreads, many quilts were expressly produced to celebrate births and weddings and, like other textile artifacts, could also serve the function of domestic memorials, dedicated to deceased persons.

By the mid-19th century, the role of quilts began to take on precise political connotations. Gradually, it became customary to give away particularly beautiful quilts as raffle prizes, or to sell them at auction and donate the proceeds to one of the two factions (Confederate or Unionist) fighting in the Civil War, not infrequently for the purchase of arms.

Further evidence of quilting’s appeal and resonance in North American culture is the ease with which different segments of the early american population embraced it and gradually transformed its identity. In all areas where english, welsh, and dutch communities settled, quilting was part of the knowledge that the newcomers brought with them from Europe. From this seed, spread over a vast geographical area, emerged a central and enduring element of the fledgling american tradition.

Quilting also flourished in the Hawaiian Islands, where native women learned the technique around 1830 from the wives of New England missionaries. Produced at a great distance from the american mainland, hawaiian quilts testify to a rapid adaptation to the local environment and artistic traditions 〈2〉. Of course, african american communities also readily assimilated quilting, adapting its procedures and aesthetics to a collective imagination in which memories of ancestral lands across the ocean and now unreachable were compounded by an awareness of a dramatic present between slavery and emancipation 〈3〉. The same happened, to varying degrees, with native american communities, marginalized by the advance of settlers and government policies of confinement and extermination 〈4〉.

Technical improvements

The history of american quilting is documented only from the mid-1700s, just before the original english colonies, in rebellion against the mother country, became a federated nation, enshrined in the 1776 Declaration of Independence.

At the dawn of the industrial age, human activities were still largely centered on the home and the family, and even in the most affluent situations, it was rare for anyone to be able to avoid domestic work in all its various articulations. Given the arduous nature of domestic work, it is likely that women in the english colonies who were able to devote themselves to quilting were a tiny minority.

Historian Sally Garoutte points out how a certain aura of legend has obscured the actual facts, in deference to the idea that the first quilts were made purely and simply as bed covers 〈5〉. With much of the female population completely absorbed in the basic tasks of daily survival, it is hard to believe that a readily available item such as quilted blankets had to be systematically made at home, taking time away from more vital activities.

The few women who devoted themselves to quilting must therefore have been economically privileged and therefore able to use the medium they knew best, fabric, not for purely practical purposes, but as a free creative expression. Indeed, many of the earliest quilts were made from scraps of fabric of little practical use, since fabric has very modest thermal properties. These pioneering works were most likely made as display and decorative pieces, which is why they are in such excellent condition.

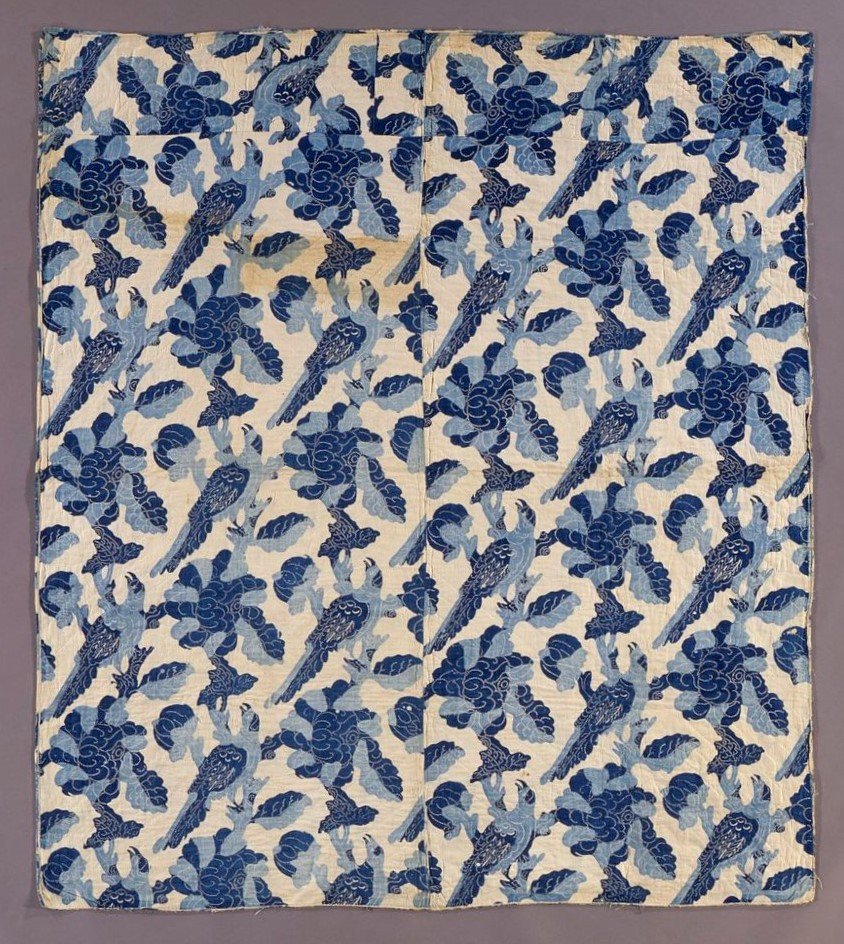

In the first half of the 19th century, the three styles already present in the british tradition were maintained in America. They were the wholecloth, whose peculiarity is that it consists of a single piece of virgin fabric suitably modified; the broderie perse, which consists of the application of patches of chintz, with its characteristic designs, to a base fabric; and finally the medallion, which develops from a square of fabric with a central motif around which other pieces of fabric are sewn, with a mosaic effect.

As evidenced by the large number of surviving artifacts, the second half of the century saw the rapid development of quiltmaking. The westward migration stimulated its production, and departing emigrants often received quilts as gifts as a reminder of their places of origin. The separation from friends and family that the wave of migration inevitably entailed was counterbalanced by a general religious awakening, which, as is always the case in situations of social transition and reorganization, proved to be particularly strong with regard to the role and duties of women. In the West, the cult of domesticity prevailed, and in this context traditionally female tasks such as sewing were pointed out as indispensable cultural and moral landmarks.

Textile artifacts outside the quilting tradition also attest to this orientation. Many embroidered samplers of the period contain phrases about the sanctity of friendship, home, family unity, and divine protection. The popular memorial stitching of photographs of the dead on decorative fabrics depicting weeping willows, urns, and graves also responds to this sensibility.

As far as quilts were concerned, the old methods were preserved and improved as much as possible, and broderie perse even gained in popularity. The criteria used to make all-white quilts became more flexible and creative; appliques were added, often in the style of broderie perse, and juxtaposed with other textile embellishments to combine different techniques and styles in a single quilt. A spectacular example of these experiments is a quilt made in New England around 1815, now in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in which the various ornaments are assembled in imitation of the flowering tree motif very common in indian palampores. Flowers, foliage, and buds were patiently cut out of plain chintz, often even padded onto the previously cut-out fabric to achieve a three-dimensional effect.

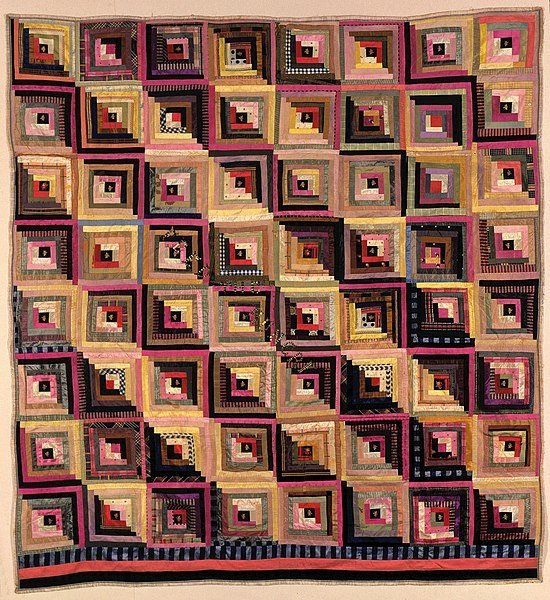

But technological acceleration was now upon us, and the compositional criterion of regular modules (the blocks) of geometric form and great simplicity of execution replaced the traditional wholecloth and medallion. Crucial to its success was its adaptability to the new mechanical medium, the sewing machine, which was increasingly present in american homes. In addition, the construction of modern transportation networks and the intensification of commerce provided access to an expanding array of fabrics, which became increasingly colorful with the advent (1856) of artificial aniline-based dyes.

These included the Star of Bethlehem, in which the eight points of the star are composed of small diamond-shaped units, the Le Moyne Star, composed of eight diamond-shaped parts, the Variable Star and the Ohio Star, both based on a central square, and the Feathered Star, a synthesis of the previous ones with the addition of a knurled border around the points. At the same time, non-star designs such as the Nine Patch, Flying Geese, and Wild Goose Chase proliferated. Appliques also appeared, no longer cut out in imitation of existing figures, but specially conceived, such as the Triple Tulip, inspired by the pomegranates depicted on palampores and chintzes.

The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, held at New York’s Crystal Palace in 1853 (and exemplified by the Great Exhibition in London just two years earlier), took stock of the young nation’s economic, scientific, and technological progress. Patriotic pride, the absence of any reverential fear of european competitors, served as a screen for many unresolved contradictions. The abolitionist movement exploded these contradictions. The demand to end slavery brought dramatically divergent interests and views into play.

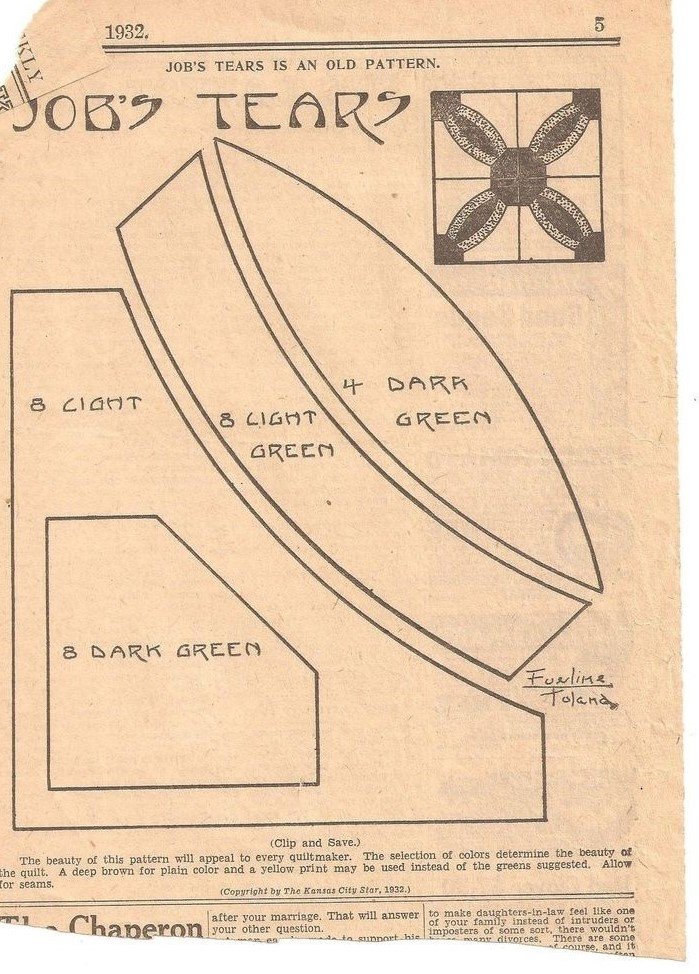

Many abolitionists routinely used quilts to promote their beliefs. Consider how Job’s Tears became Slave Chains, or how a new pattern, the North Star, was named in homage to the North Star that was supposed to guide runaway slaves to freedom 〈6〉.

The Civil War

In the presidential election of 1860, Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party embraced the anti-slavery cause in radical opposition to the southern states, which felt their constitutional rights were being violated. Lincoln was elected President, but before his inauguration, seven southern states, whose economies were based on cotton plantations and the cheap labor of black slaves, seceded from the Union to form the Confederacy. The casus belli occurred on April 12, 1861, at Fort Sumter, when the Confederates attacked the Union defended fortress until it surrendered. The war, bloody and fraught with consequences never fully healed, ended on June 23, 1865, with a Union victory and an estimated death toll of at least 700,000.

Neither side was prepared to fight it, let alone think it could last that long. Women on both sides worked for their troops 〈8〉. The quilts they made were used daily on the battlefields, while in the rear they served to raise funds needed to purchase everything from cannons to bandages for wounds. But when needed, they could also serve as emergency covers, doors and windows, and shrouds for the dead. Sewing circles and other charitable organizations were transformed into institutions to support the fighting men, and country fairs and entertainment shows were organized for this purpose.

For the Unionists, the production of quilts specifically designed to protect soldiers from the cold at the front can be quantified to at least 250.000 pieces. Many of them contain thoughts, messages and greetings embroidered by women for their husbands, sons, brothers and fathers under arms. A message embroidered on a quilt by a mother:

«My son is in the army. Whoever is made warm by this quilt, which I have worked on for six days and most of six nights, let him remember his mother’s love» 〈9〉.

While high-quality quilts (often family heirlooms) were used to raise money and ended up in the homes of donors, those sent to the troops were rarely spared destruction. Some were made in groups, with each patchwork square representing a share of the money. Sometimes school classes were assigned to make them, dividing the work between boys and girls.

Southern women also mobilized to provide essential goods for the troops, but with much more limited resources. In 1861, the textile industry was virtually nonexistent in the South, which was also under a severe embargo. As a result, women engaged in home production by spinning, carding, and weaving, often learning these skills from black slaves who already practiced them. Little remains of the poorer and more easily worn quilts on the confederate side. However, it is certain that they were among the most commonly traded items in the very harsh postwar years, when bartering was often used in the South to pay for basic necessities.

Typically, quilts made between 1850 and 1875 were characterized by an unprecedented spirit of experimentation. Any available material, from silk to raw wool, calico to cotton, in the most varied colors and prints, could be used. For the women who devoted themselves to it, the creation of quilts took on the flavor of a competition in which unusual geometric shapes, dazzling colors, and patterns of difficult and sophisticated composition offered ever new targets. Ancient techniques were adapted to a more modern and aggressive taste.

The extensive use of appliqué resulted in a type of quilt based on the repetition of a single element over the entire surface. Botanical motifs then appeared. The favorite color combination was red and green, juxtaposed with bright white, with the occasional addition of yellow and orange. Around 1870 and through the end of the century, red gave way to pink, resulting in a pattern called Double Pink, which consisted of light pink printed fabrics with dark pink motifs, often juxtaposed with green appliqués.

Women’s magazines began to publish patterns for home quilting. A popular pattern for silk was the One Patch Hexagon, of which the Honeycomb and Mosaic were two successful derivatives. Another popular pattern was the one known as Blocks, Tumbling Blocks or Baby Blocks, which consisted of diamond-shaped blocks. The Log Cabin, probably created after the Civil War, was a great success. One from 1866, from Missouri, has survived, created to raise funds for the families of former Confederates: a very interesting detail is the motto “Feed the hungry” stitched in sequins in the center of the work.

It should be added that for several more decades, the various motifs in use were not known by their current names, either because they were defined differently from place to place, or because the custom of referring to a generic parental figure prevailed; Grandmother’s Quilt, Mom Loved Blue Quilt, Aunt’s Flower Quilt, as in gastronomy for certain dishes or drinks. It was not until the beginning of the 20th century, with the publication of the first specialist books and magazines, that the best-known patterns were given proper names.

Postwar and turn of the century

The industrial and financial boom that followed the Civil War was vigorous, facilitated by new means of transportation, especially railroads, and communications; telegraph and telephone. Rising school enrollment reduced illiteracy, though with the inequitable treatment often reserved for women. Increasing prosperity was tangible, but for women, who were generally underpaid, work in textile and garment factories was the most common opportunity. However, professional positions such as teachers and nurses, as well as activism in voluntary groups, introduced new elements. These elements formed the basis of Social Housekeeping, a women’s movement that, although within a traditionalist framework marked by domestic and religious values, emphasized the dignity of women by demanding their political and social equality.

Industrial development greatly influenced home quilting. In urban centers, interest in the practice waned as the product was now available in mass-produced patterns sold at low prices. In rural areas, however, the tradition continued. The end of the 19th century is considered by experts to be a period of decline. Elegant chintzes were no longer used, and the more complex work disappeared from the repertoire.

Through their influence, trade journals began to limit the repertoire of decorative inventions by suggesting the most fashionable patterns to their readers from time to time. For their part, the anabaptist amish communities began to signal themselves as producers of quilts with simple and chromatically intense compositions.

In the decorative realm, the divide between rural and urban culture became apparent. While victorian tastes persisted in the countryside, Arts & Crafts and Art Nouveau tastes took hold in the cities. Cotton seemed outdated, and women more in tune with the new trends favored silk and wool, not to mention velvet and plush.

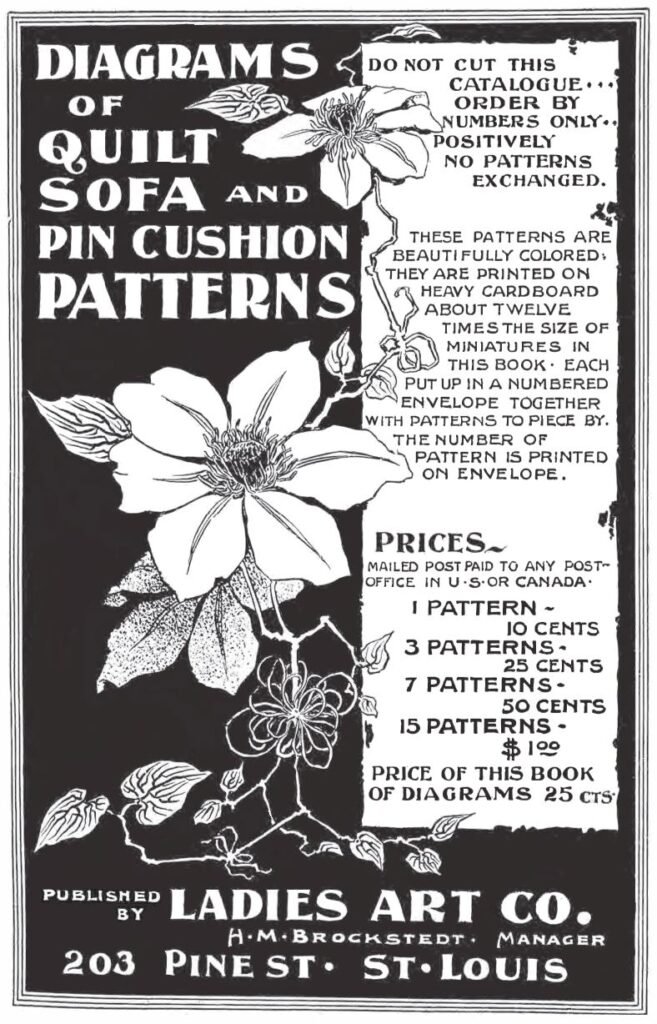

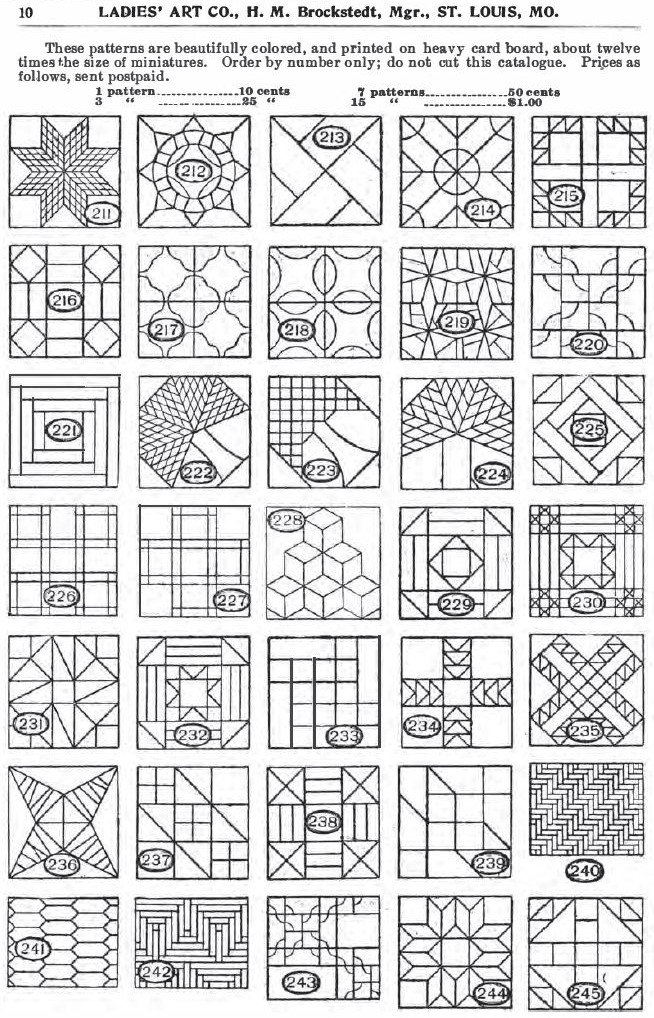

Although now obsolete, traditional patchwork cotton quilts continued to be made, updating and varying the old patterns, now under the direct control of the media interested in the subject. In 1889, the Ladies Art Company, a company that had just started in St. Louis, Missouri, to disseminate and market quilting techniques, published the first issue of Diagrams of Quilt Sofa and Pin Cushion patterns, or paper patterns for making sofa quilts or for use as cushion covers.

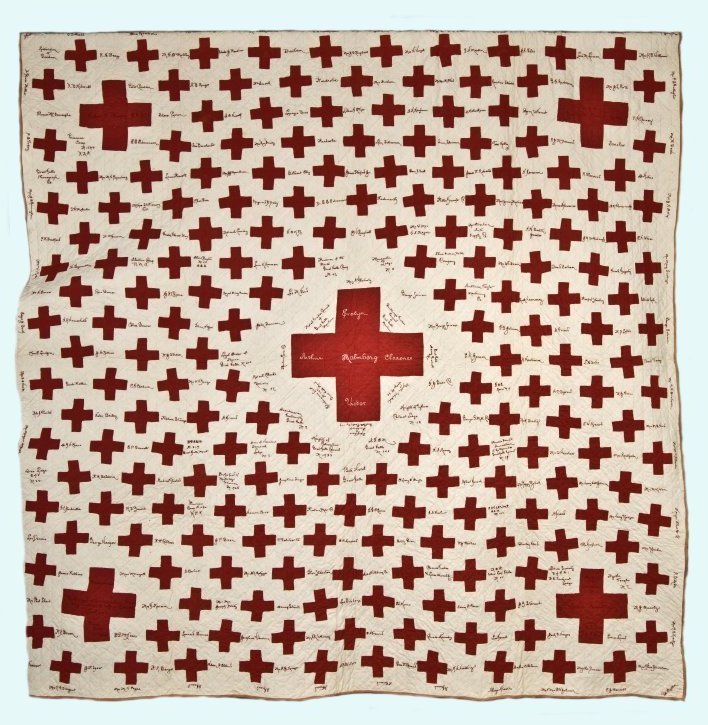

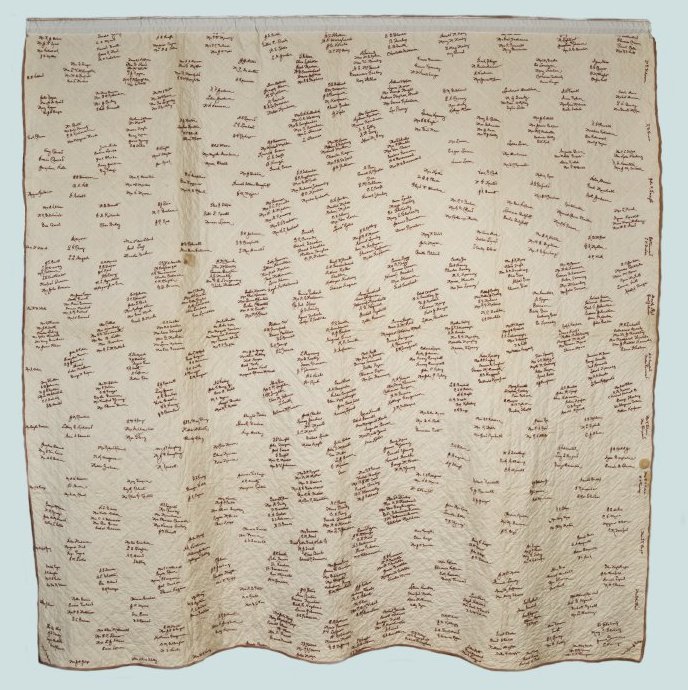

Another cause funded by quilt sales was the fight against alcoholism. Movements such as the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) addressed such sensitive issues as the eight-hour workday, the difficulty of working women in caring for their children, the prison system, and women’s suffrage. This goal would be achieved in 1919, at the end of World War I. Quilts were also used to finance these initiatives. The signed quilts were particularly successful, generating two forms of income; the donation required of those who wanted to put their signature on the fabric, and the proceeds from the sale of the quilt when it was finished.

The price of signing a quilt varied according to the position desired. Writing one’s name in the center of the composition cost between twenty-five and fifty cents. More off-center positions were worth between two and ten cents. This particular type of quilt is almost obsolete today, and yet there are charitable organizations, such as the Mennonite Central Committee, an organ of anabaptist christian communities 〈10〉, that still use them.

The 20th Century

Memories of the Civil War seemed long gone when the United States, under President Woodrow Wilson, sided with Germany and Austria in World War I in April 1917 and sent its troops across the Atlantic until the conflict ended in November 1918.

Housewives were urged by the government to make quilts that could be purchased in stores and shipped to soldiers serving in Europe. In 1918, to add luster to the initiative, many newspapers and magazines published the slogan “Save the Blankets for Our Boys Over There”. The campaign was very successful 〈11〉.

In September 1918, the magazine “Modern Priscilla”, which had published instructions for making a quilt to raise money for the Red Cross late the previous year, offered its readers four quilt designs, called Liberty Quilts, that could be easily made at home, one of which could be made with a sewing machine. The practice of making signed quilts as a fundraiser, which began during the Civil War, was revived to support families whose members had been killed in the war.

The Roaring Twenties were prosperous and creative. Automobiles became the most sought-after American product in the world, writers such as Ernest Hemingway and Francis Scott Fitzgerald achieved international fame, and jazz music quickly spread abroad. Hollywood actors, often of european descent, such as Rodolfo Valentino, Greta Garbo, and Charlie Chaplin, embodied the burgeoning phenomenon of movie stardom. Among the quilts testifying to the continuation of this enthusiastic climate, many were dedicated to the feat of aviator Charles Lindbergh, who in 1927 flew solo across the Atlantic Ocean in thirty-six hours aboard the Spirit of Saint Louis.

The out-of-control spiral of consumption, overproduction, and business contributed to the financial collapse of 1929, which wiped out more than nine million bank accounts, caused hundreds of thousands of people to lose their jobs, led to the bankruptcy of several companies, and had severe global repercussions. Starting in 1933, with the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, proponent of the new political-economic course called the New Deal, a series of measures were launched to combat the severe economic and employment crisis.

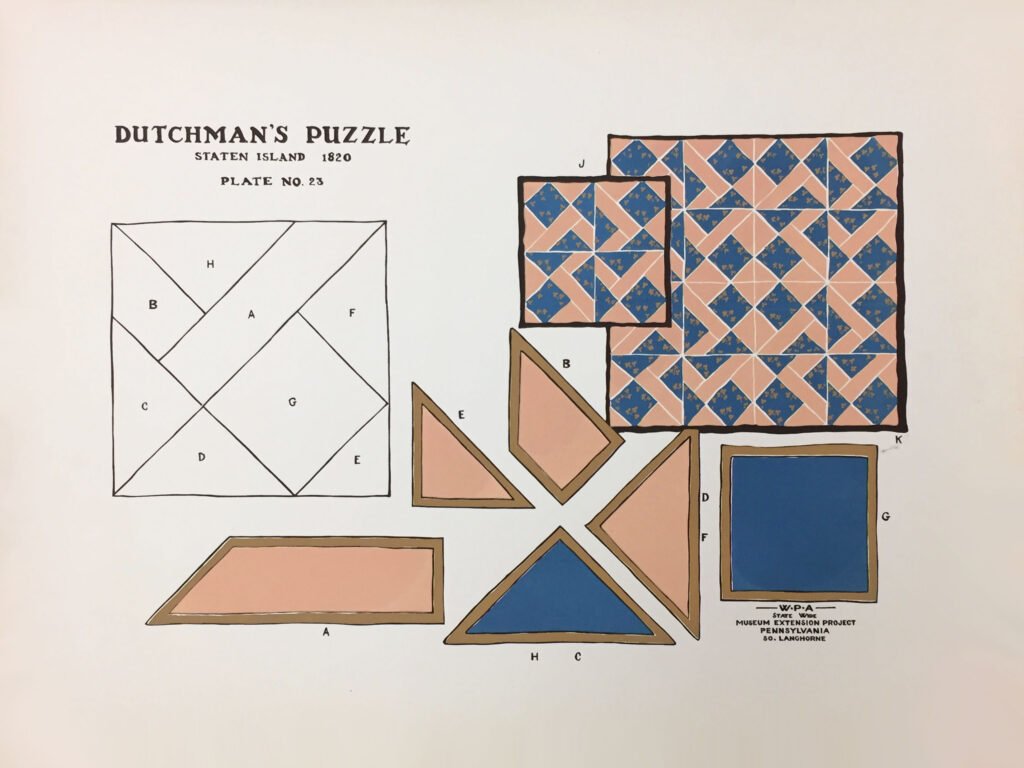

During the difficult years of the Great Depression, efforts were made not only to improve the country’s financial situation, but also to improve the mood of its citizens. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was concerned with the development and promotion of the arts, including quiltmaking. One example of the WPA’s work was the establishment of arts and crafts training projects in the Appalachian Mountains, North and South Carolina, and the Midwest. All areas of weaving, sewing, and quiltmaking benefited 〈12〉.

Another WPA initiative was the American Design Index, a census of artistic evidence and folk traditions, from naive painting to games to textile artifacts, including quilts. The quilt category appeared in most of the thirty-five states indexed. In short, the tradition of quiltmaking was increasingly elevated to the status of an artistic creation. Its utilitarian nature was sidelined in favor of emphasizing its cultural and folkloric aspects.

The Century of Progress Exhibition, held in Chicago in 1933-34 to celebrate the city’s centennial, attracted some twenty million visitors. For the occasion, a national quilting contest was held, sponsored by the department store chain Sears, Roebuck & Company, with a $1,000 prize for the winning entry and several smaller prizes 〈13〉. The winner was Margaret Rogers Caden’s quilt Unknown Star, later renamed Feathered Star, which the author presented to First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt.

The contest was very well attended, a sign of the renewed popularity of quilting and traditional arts and crafts in general during the Great Depression. In the eyes of the public and the press, quilts were among the objects most representative of this mood. Quilts were regularly represented at the great fairs that were gradually organized to support and revive national production.

With the outbreak of World War II, women took the place of men in industries whose male personnel were under arms. The iconic figure of Rosie the Riveter became the symbol of the patriotic, hardworking and energetic woman. The “V” of Victory, found on many quilts of the time, gives the measure of the physiological creative flattening that occurred in such a particular historical phase 〈14〉.

With the end of the war, the fortunes of quiltmaking took a turn for the worse as more and more women found employment that took them out of the home. Kits containing everything needed to make a quilt, which were introduced in 1910, enjoyed great commercial success at the turn of the 1940s and 1950s. While it is true that their proliferation favored the popularization of some now-standard designs, it must also be said that it favored the learning of the basic rudiments by new generations.

The repeated waves of migration from the poor countryside to the cities that promised well-paying jobs accentuated the provincial and residual dimension of quiltmaking. It was now up to the women left behind in rural areas to keep the tradition alive. Certain regions of Deep America, such as Kentucky, began to brand themselves as the home of fine quilting, in accordance with the strictest canons of tradition.

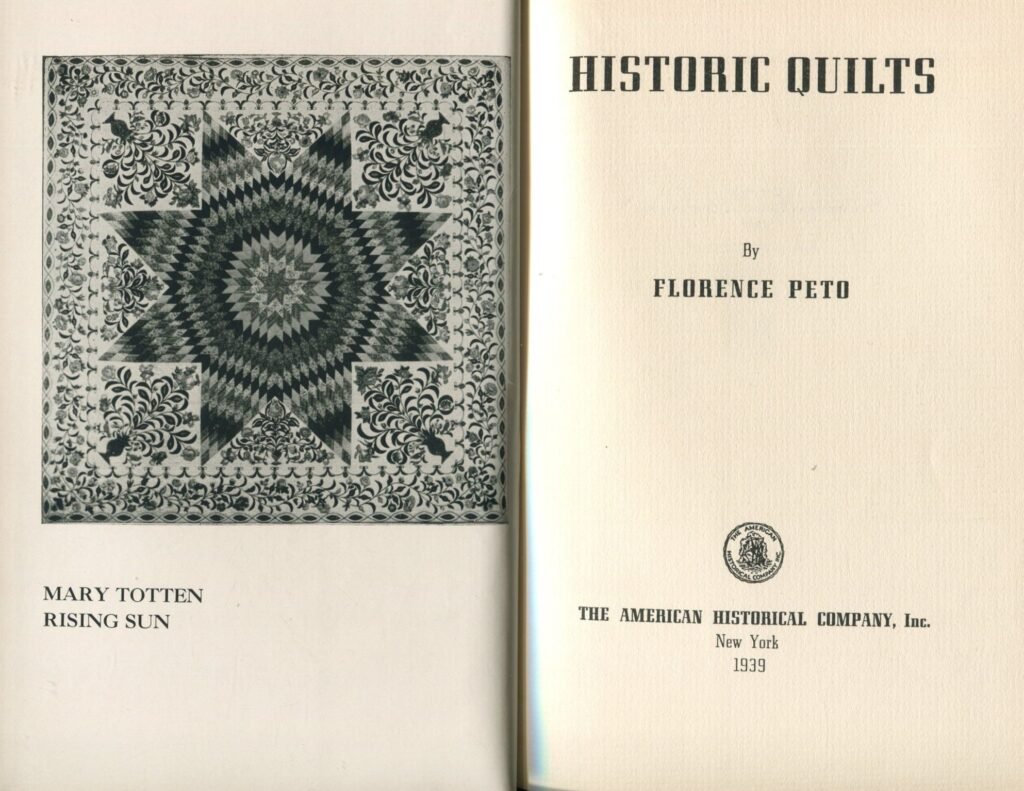

The revival of quiltmaking, understood as a body of knowledge grafted onto the original american tradition, effectively came to an end around 1940. On the other hand, its consecration as an art tout court began, coinciding with the interest shown by museum institutions. An early example is the exhibition of Rose Kretsinger’s work organized by the Kansas City Art Institute in 1939. Similarly, in 1943 the Art Institute of Chicago exhibited several works by quiltmaker Bertha Stenge, and in 1948 the New York Historical Society exhibited quilts owned by scholar and collector Florence Peto.

The exhibition season represented a promotion of quiltmaking in the field of art history, giving visibility to experts, collectors, museums, books, and catalogs devoted entirely to quilting and its history. While this dynamic fostered the emergence of distinct and recognizable artistic individualities, it also eliminated one of the founding elements of quiltmaking; group work, in the name of sharing and anonymity.

The latter aspect survives to a certain extent in the activity promoted by the many quilting associations that allow quilters all over the world to meet and exchange ideas, cultivating a discipline that, while referring to the craft traditions originating in the United States, does not shy away from the conceptual and perceptual challenges typical of contemporary art.

〈1〉 A reference for the history of quilting in the United States; R. Kiracofe, M.E. Johnson, The American quilt: a history of cloth and comfort, 1750-1950, Clarkson Potter, London-New York 1993. Among the most authoritative websites are: www.americanquilter.com (official website of the American Quilter's Society), www.quiltershalloffame.net (official website of the Quilter's Hall of Fame and its museum in Marion, Indiana, with the biobibliographical profiles of all the individuals - quilters and researchers/scholars - inducted into the Hall of Fame), www.internationalquiltmuseum.org (official website of the International Quilt Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska).

〈2〉 See P. Serrao, J. Serrao, The Hawaiian Quilt. A Spiritual Experience, Mutual Publishing, Honolulu 2007.

〈3〉 See C. Benberry, Always There: The African-American Presence in American Quilts, The Kentucky Quilt Project, Louisville 1992.

〈4〉 See M.L. MacDowell, C.K. Dewhurst (a cura di), To Honor and Comfort. Native Quilting Traditions, Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe 1997.

〈5〉 R. Kiracofe, M.E. Johnson, The American quilt: A History of Cloth and Comfort, 1750-1950, cit., p. 46.

〈6〉 The Underground Railroad was the code name given to the network of clandestine shelters and transports (made possible by the solidarity of abolitionists) by which fugitive slaves from Southern states sought to reach Northern states that had already abolished slavery or Canada. The North Star was one of its best-known symbols. See R.J.M. Blackett, Making Freedom. The Underground Railroad and the Politics of Slavery, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 2013. A novel; C. Whitehead, The Underground Railroad, Doubleday, New York 2016.

〈7〉 On the history of the American Civil War, the studies of Raimondo Luraghi are fundamental, and not only in Italy. See R. Luraghi, Storia della guerra civile americana, Einaudi, Turin 1966, and La guerra civile americana. Le ragioni e i protagonisti del primo conflitto industriale, Rizzoli, Milan 2013.

〈8〉 See P. Weeks, D. Beld, Civil War Quilts, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen (Pennsylvania) 2011.

〈9〉 Quoted in R. Kiracofe, M.E. Johnson, Op. cit., p. 110.

〈10〉 The official website is www.mcc.org. On quilting in Amish and Mennonite communities, see R.T. Pellman, J. Ranck, Quilts Among the Plain People, Good Books, Lancaster (Pennsylvania) 1981.

〈11〉 See S. Reich, World War I Quilts, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen (Pennsylvania) 2014.

〈12〉 See M. Waldvogel, Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quiltmaking and the Great Depression, Rutledge Hill, Nashville 1990. Also useful is the website A New Deal for Quilts, https://newdealquilts.janneken.org/

〈13〉 See B. Brackman, M. Waldvogel, Patchwork Souvenirs of the 1933 World's Fair. The Sears National Quilt Contest and Chicago's Century of Progress Exposition, Rutledge Hill, Nashville 1993.

〈14〉 See S. Reich, World War II Quilts, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen (Pennsylvania) 2017.

Homepage: Women from Gee's Bend, Alabama, at work on a quilt during the Magic City Art Connection at Linn Park in Birmingham in 2005 (photo credits André Natta/Wikimedia).

Below: the Seattle Quilt Manufacturing Company in an anonymous photo circa 1920 (University of Washington/Wikimedia).