by Francesca Alinovi

In her all too brief career as an art historian and critic, Francesca Alinovi (1948-1983) repeatedly addressed the themes of decoration and decorum. Her approach was inextricably linked to the new artistic trends that she advocated and theorised, both in Bologna (the city where she lived and worked) and in New York, the favourite destination of her travels. What we are presenting is the most organic essay that Alinovi dedicated to decorative themes. It is still very interesting today, pregnant with the passion of someone who pursues a militant point of view, but at the same time cultivates broad and in-depth studies. In addition to authors who, in those years, marked the transition from modernism to post-modernism (Jencks, Mendini, Moles, Poggioli, Venturi), we find texts as old as Carlyle's Sartor Resartus (1836) and Musil's On Stupidity (1937). The artists and critics of the "Pattern and Decoration" group are particularly prominent, but there is no shortage of references to the Italian scene. Terms that are now abused and discredited, such as "populism", regain their original vitality here. Il ritorno alla decorazione nell'arte, nell'architettura e nel "design" (we have decided to remove the quotation marks from this last word to adapt it to current usage) first appeared in "Rivista di Estetica", no. 12, 1982, then in the posthumous volumes of Francesca Alinovi's writings: L'arte mia, Il Mulino, Bologna 1984 and, edited by M. Bergamini and V. Santi, Francesca Alinovi, Postmediabooks, Milan 2019. The English translation and the selection of images accompanying the text are by Enrico Maria Davoli. Many thanks to Brenna Alinovi and the editorial staff of the "Rivista di estetica" for authorising this online republication.

1. Decorum is a sin

The recent resurgence of decoration in art, architecture and design, which has taken place with a vengeance over the last decade, has unsettled practitioners in the various fields and reopened a debate on the goodness or otherwise of decoration that had seemed to have been shelved since at least the beginning of the century. This is because the concept of decoration, seemingly marginal and secondary, a trifle in comparison with the most important issues, touches on a system of values that ranges from the level of morality to that of good taste. In fact, it must be said at once that in our Western culture, despite their original meaning, terms such as decorum and ornament have a pejorative connotation, ranging from the accusation of immorality to that of indecency. Decoration is a taboo, a dangerous and contagious vice that undermines the correct and linear structure of our ideal culture. Decoration, in fact, goes hand in hand with a taste for low, primitive, popular or regressive culture – regression to childhood, uncultivated, instinctive and unclear – and it does not fit in with the plans of a cold and clear rationality, coherent and progressive, aimed at eliminating all kinds of frills, frivolities and conveniences.

But decoration, whether we want it or not, whether we accept it or not, frames all the ordinary manifestations of our existence; it is nevertheless given as a habitual datum of our daily perception; clothes, make-up, domestic and urban furnishings, utensils, accessories, art and mass media images, colours, textiles, objects. Every painting, every sculpture, every piece of furniture, every piece of architecture is always also an ornamental product; an embellishment of the bare walls that enclose us, a filler of the emptiness that annihilates us, a familiar and protective adornment of the inhospitable surface of our planet.

But decorum is a sin; because the idea of decorum contradicts one of the firmest convictions of our culture, of very ancient origin but somewhat consecrated by the Modern Movement, that of “truth against the world” 〈1〉. That is to say, the ideals of simplicity and reduction correspond “by nature” to the values of truth and beauty. Truth is naked, and even Adam in his paradisiacal Eden, though still full of colourful flowers and luxuriant vegetation, openly displayed the nakedness of his anatomical truth. Truth, then, is also beautiful, in harmony with the laws of nature.

Decorum, on the other hand, is false and artificial, superimposed on nature by falsifying and disguising it. In fact, decorum is one of the oldest forms of artifice and coincides with the earliest beginnings of civilisation, as it is one of the most subtle and sophisticated means devised by man to correct, transform and beautify his own bodily and environmental accidentality. Among the earliest manifestations of decorum, a mixture of artifice and culture, are tattoos applied directly to bare skin and clothing designed to disguise the natural body. In one of the best-known and most provocative texts on decorum, Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus 〈2〉, we read: «The first purpose of Clothes […] was not warmth or decency, but ornament. […]. Nevertheless, the pains of Hunger and Revenge once satisfied, his [of the primitive man] next care was not Comfort but Decoration (Putz ). Warmth he found in the toils of the chase; or amid dried leaves, in his hollow tree, in his bark shed, or natural grotto: but for Decoration he must have Clothes. Nay, among wild people we find tattooing and painting even prior to Clothes. The first spiritual want of a barbarous man is Decoration, as indeed we still see among the barbarous classes in civilised countries» 〈3〉. And again, «Clothes gave us individuality, distinctions, social polity, Clothes have made Men of us […]» 〈4〉.

A fact not to be overlooked: in this book whose title means Patched Tailor and which is presented as a “Philosophy of Clothes” 〈5〉, Carlyle pretends to comment on the work of an imaginary German philosopher, a contemporary of Goethe, whose emblematic name, Teufeldröckh, means “Devil’s Mud”. Naked man was moulded into clay by the hands of God; clothed man was born from the mud of the devil. Clothing made us men, but rebellious and damned men. After the original sin, Adam had to cover the nakedness of his body. The adornment is thus linked to the idea of sin, the original sin and the rebellion of man who, transgressing the divine will and freeing himself from his subordination to nature, asserts his will for cultural autonomy, facing with toil and pain his own lonely impact against the hard earthly crust of the planet.

2. Decorum is ugly

Decorum is one of the original forms of art and culture; it’s one of the hallmarks of our humanity, but it’s generally associated not only with sin, but also with the idea of “ugliness”. Decorum seems to be one of the greatest offences against good taste in our culture.

Decorum is ugly not only because it’s false and artificial, and therefore sinful, but also because it violates those canons of simplicity, coherence and reduction to which, as I said, the idea of beauty traditionally corresponds. Decorum is, by definition, excessive, exuberant, complex, chaotic and indeterminate. What’s more, it is serial and repetitive; it reflects – or rather prefigures – the iterative modes of dissemination typical of mass production, the mechanisms of easy reproducibility inherent in mass culture. Decorum, in other words, denies the assumptions of uniqueness and originality inherent in what has for centuries been defined as Artwork, with a capital A.

In fact, the suspicion arises that the pejorative meaning of decorum has somehow worsened in our time, precisely because of this similarity, precisely because it is alien to the always rare and unrepeatable exceptionality of the work of art and close to the quantitative mechanisms of mass culture. Decorum has always been based on reproduction and imitation, in short, on easy comprehension, aimed at winning over public taste. Mass culture, ashamed of its own rapid and effective systems of dissemination, retaliates against Decorum by branding it with the epithet Kitsch.

The word decoration is now synonymous with Kitsch, and Kitsch is a concept that is inseparable from the masses, that is born, grows and evolves with them, nestling like a parasite in the folds of their success. The triumph of Kitsch is the price culture pays for the triumph of culture itself, which has never been more widespread, more loved, more sought after. But a price for what? Why is Kitsch also interpreted as an evil and negative phenomenon?

The revival of decoration in recent years has led to a less uncompromising attitude towards kitsch. It’s clear that a culture such as ours, which prefers less to more, the authentic and true to the fake, quality to quantity, the unique to the copy, and which condemns ornamentation as a crime, cannot help but despise as monsters born of impure birth the hybrid, polluted, numerically unlimited products proliferated by a chaotic, excessive and exuberant mass consciousness.

Kitsch has become part of our aesthetic taste; Abraham Moles, in what can be considered the most brilliant and subtle analysis of Kitsch to date, published in 1971 and translated into Italian in 1979 under the title Il Kitsch. L’arte della felicità 〈6〉, after analysing the historical and etymological origins of the word, coined in German around 1860 to mean “piling up”, “stocking in bulk”, “falsifying”, “counterfeiting”, ends up not so much singing the praises of Kitsch as simply acknowledging its legitimacy of existence, its pure raison d’être.

In other words, Kitsch is not the bogeyman of respectability, the sword of Damocles hanging over the heads of honest and civilised people, but rather the most important, and perhaps the only possible, current sentiment within affluent society, a society based precisely on quantity, excess, waste, and fast and furious consumption.

In short, Moles recognises Kitsch‘s right to exist, not on the basis of an aesthetic and moral judgement (Moles doesn’t care whether Kitsch is beautiful or ugly, good or bad), but simply on the basis of historical and cultural considerations. Kitsch is not a defined and delimited style, but a general “way of being” 〈7〉, a universal way of feeling, communicating, living, enjoying. Kitsch is the result, in today’s mass society, of the victory of the average over the elite, of the mediocre over the exceptional, of art for all over the art of the few. Kitsch is the art of happiness because it allows everyone, even the masses who have been excluded from culture for centuries, to enjoy simple, accessible and pleasurable products. Kitsch is ordinary art, “on a human scale” 〈8〉, whereas traditional fine art was extraordinary and out of proportion.

While Moles makes no qualitative judgments, he does take as his model the dirtiest products of the popular imagination, such as souvenirs, postcards, ex-votos, oleographs and gadgets; a few years ago, in 1978, in New York, a museum director, Marcia Tucker, presented at the New Museum an unusual exhibition deliberately inspired by ugly or bad painting, “Bad” Painting 〈9〉, dealing with the problem of Kitsch from the point of view of its inclusion in the visual arts.

Tucker’s choice of “ugly” works are those of amateurs, not professionals, with the exception of the two star artists 〈10〉. Such works, as the catalogue says, are not ugly in themselves from the point of view of workmanship, but they are ugly in that they are too familiar, easy, repetitive and even funny. In short, they are simply too close to average and popular taste, stereotype and Kitsch.

Tucker, quoting a passage from Renato Poggioli’s Teoria dell’arte d’avanguardia 〈11〉, points out how such a conception of the ugly, that is, based not on intrinsic considerations, internal to the work, but on external motivations relating to the novelty or otherwise of the style and its new or already known character, was entirely alien to classical aesthetics. The beautiful and the ugly were traditionally distinguished on the basis of their respective formal virtues or faults and imperfections. Today, on the other hand, ugly works are judged as works that might be better defined as «to have a not-new beauty, a familiar or well-known beauty, a beauty grown old, an overrepeated or common beauty: all synonyms that could serve to define kitsch or stereotype» 〈12〉.

Mass culture is self-punishing, ashamed of its own ease and happiness, and needs art to distinguish itself, to be difficult and unhappy. Historical avant-gardes are the best interpreters of this message, formulating for themselves a cryptic and indecipherable language, comprehensible to a few and inaccessible to most, based on constant innovation, transgression and the abolition of any form of pleasure.

3. Decorum is stupid and trivial

Two other negative connotations usually associated with decoration are stupidity and triviality. A decorative motif is simple and therefore stupid (you don’t have to be clever to understand it); it’s pleasant and therefore trivial (everyone likes it as it’s a regular hit product).

That art, in order to be art, must be intelligent and exceptional, and must express itself through incomprehensible messages, it has been said, is an eagerness typical of the historical avant-gardes, which, in the face of competition from the mass media, claim for themselves an elitist, incommunicable language. On the other hand, within the historical avant-gardes there have also been demonstrations to the contrary. Dadaist artists, for example, used stupidity to provoke intelligence. Of course, it’s also true that Dada wanted to achieve a more refined and perfect form of intelligence through the low, left-handed and irritating blows of stupidity.

Decoration, on the other hand, hides no provocative purpose, no desire to camouflage under the frills of frivolity an armed aggression aimed at striking intelligence in the heart. Decorative art appears for what it is, transparent: no more or less than what is seen, geometric and floral patterns that stand there, decorating a surface. An art that appeals to children and the elderly, to the uncultured and the intellectual. To see a beautiful decoration is a pleasure for everyone, and it is surprising how much pleasure can be derived from an utterly useless exercise, a pure exercise for the pleasure of the eyes and the senses.

But stupidity, it is well known, borders on intelligence. And just as in certain situations it is difficult to establish the boundary between the beautiful and the ugly, so it can become impossible to separate the stupid from the intelligent. It is no coincidence that an old text by Musil, On Stupidity 〈13〉, was reprinted in Italian in ’79, just at the time when the success of decoration was reviving interest in stupidity. In the same years, there was also talk of “screwball” in the field of music.

In this essay, a transcript of a lecture given in Vienna in 1937, the author of The Man Without Qualities draws a unique analogy between Kitsch (and one might even say decoration, given the close resemblance between the two concepts) and stupidity, as between the two sides of the same coin. Kitsch and stupidity, the former in the sense of an invalid, inadequate commodity and the latter in the sense of an invalid or inadequate intelligence, have in common a series of negative attributes that are difficult to summarise in a single word: they are both vulgar, morally repugnant, indecent, but above all quantitatively exuberant, numerically surplus.

Quantity, in short, distinguishes the bad from the good, and quantity distinguishes the stupid from the intelligent: a chaotic, emotionally uncontrolled, panicky quantity. The panic of overflowing commodities is equivalent to the panic of confused gestures, without the clear linear direction that intelligence provides. The stupid, according to Musil, differs from the intelligent not because his actions are really stupid, idiotic, but because the guiding criterion that directs them is not a rigorous plan, but the indistinct mass of undisciplined actions dictated by emotion and instinct. That is why the stupid man, who, instead of a single, deliberate and decisive gesture, makes a thousand actions aimed at uncertain goals, is much more like the archaic and primitive man than the civilised man. The fool, in other words, merely adopts the rudimentary modes of action, closer to feeling than to reason, that are characteristic of primitive behaviour. On the other hand, and this can be clearly seen in the case of the artist and the poet, there are certain forms of legitimised stupidity in our society, which even become the object of appreciation. «Simple stupidity», Musil writes, «is often truly artistic» 〈14〉. And again: «If true stupidity is a silent performer, intelligent stupidity is what contributes to the busyness of intellectual life, and especially to its instability and fruitlessness […] There is practically no important thought that stupidity cannot use; it is mobile in every sense and can wear the clothes of truth. Truth, on the other hand, has only one garment at a time, and only one way, and is always at a disadvantage. Stupidity is not a mental disease, but it is the most dangerous disease of the mind, dangerous even to life» 〈15〉.

Stupidity, according to Musil, borders on genius, and no art can be created without a component of stupidity. The same could be said of kitsch and ornamentation; every art has always possessed, in addition to elements of novelty and originality, kitsch and decorative aspects, those capable of making the product acceptable both to the public and to the taste of its patrons, and even to that of its author.

Kitsch and stupidity are therefore ingredients of art, as is banality. The concept of banality has been developed in recent years, both theoretically and creatively, by Alessandro Mendini, author of the preface to Moles’s book and promoter of numerous initiatives, including on the practical-productive level, in collaboration with Studio Alchimia in Milan, directed by Alessandro Guerriero, resulting, among other things, in an exemplary exhibition, L’oggetto banale 〈16〉.

Mendini’s banal is related both to Moles’s Kitsch and to Musil’s stupidity, but above all it is identified with decoration, and comes directly from the change in optics and perspectives brought about by the entry of decoration into art, design and architecture.

It must be said that Mendini not only justifies the banal, identifying its historical and psychological reasons, its philosophical and anthropological motivations, but also goes deeper, trying to visualise the banal, transforming it from ideas into concrete forms, producing a series of objects and furniture in the same years, between ’78 and ’80.

The banal, as Mendini describes it, is a phenomenon of taste which, like Kitsch, is based on inauthenticity and, like stupidity, on quantity and sentiment, but which, unlike Kitsch, deliberately avoids flashy and sensational images, rejects blatancy and excess, and takes place quietly, unobtrusively and modestly, elevating mediocrity to its own principle of poetics.

«Banal», writes Mendini, «means becoming aware of the everyday […] Banal is a political fact directly linked to the strength of the bourgeoisie, it is the Trojan horse of the popular masses to reappropriate art […] Precisely because it is capable of establishing the “true” relations of people, hour by hour, with the objects that surround them, banal proves to be that certain aesthetic, that real creative capacity, that formal model that is really established in the greatest number of individuals. Banality is applied art, adapted to everyday life». 〈17〉.

4. Decorum is not “aut/aut” but “both/and”

Mendini expresses a considerable form of respect for the lower-middle taste of the common man. And all the problems that have arisen in recent years in connection with decoration revolve precisely around this capital point, that is, the revaluation by occidental culture of marginalised, eccentric, peripheral cultures: popular and mass culture, feminine and “colour” culture. Decoration is rooted in programmatic vulgarity, understood in the etymological sense of the word vulgus, art for the vulgar: be it the compact and uniform mass of occidental culture, or the mixed and highly differentiated, hybrid people of non-occidental countries. Decoration is a populist art form before it is popular, and it is inclusive: it wants to encompass and include everything, department store and street decoration, exoticism and nationalism, craftsmanship and industrial production, the already made and the yet to be made. And it wants to speak all languages, to create a universal slang.

We have already seen how decoration throws into crisis the traditional categorical distinctions between beautiful and ugly, true and false, stupidity and intelligence, trivial and original. It might be added here that decoration undermines many other dichotomies, such as those between old and new, occidental and third world, male and female, useful and useless, surface and depth. Decoration replaces the principle of exclusion set up as a system by modernism with the logic of inclusion, the antithesis of “aut/aut” with the aesthetics of “both/and”, and the old dualisms with the effective co-presence of opposites, always very embarrassing for the purposes of scientific analysis.

I will now refer to the first texts on decoration that appeared in the United States between the end of ’76 and the course of ’79. It must be said that, although this phenomenon has since had many and diverse applications, in painting it was born in the mid-1970s from the lucky meeting of two young artists, then students, Robert Kushner and Kim MacConnel, with a critic, Amy Goldin, a teacher at the University of San Diego in California. This lucky meeting, which took place among the desks of the university’s lecture halls, had a decisive epilogue when, during a trip to Iran, the three of them, fascinated by the decoration of textiles, embroidery, carpets and Islamic ceramics, sensed the possibilities of a new ornamental art. The origins of decorative painting, which Goldin herself defines as Pattern Painting, are thus rooted in the somewhat unusual, but very promising, marriage between what must be considered the symbolic occidental culture, American, and what is one of the cornerstones of non-occidental culture, Islamism. The result of this hybrid union is a highly eclectic and composite art form that, because of its mixed characteristics, has often been associated with postmodernism.

Interestingly, all the texts on decoration partly coincide with the theses elaborated around post-modernism, and partly differ from them. Charles Jencks, for example, in his famous book, The Language of Post-modern Architecture , curiously does not attribute any special role to decoration, although later in the course of his discussion he makes constant references to the new importance assumed by decoration in architecture. Such an oversight, if one can call it that, is not accidental. Postmodernism, as Jencks sees it, and as many others after him will continue to see it, is limited to an emphasis on contextualization, nationalism, ethnic and vernacular languages, historicism, eclecticism, or what, as Andrea Branzi has aptly defined it, could also be called neo-academia 〈20〉. Postmodernism, although Jencks does not fail to cite Venturi’s text, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture 〈21〉, where precisely the inclusive formula of «both/and» is elaborated for the first time and the aesthetic potential of an architecture laden with ambiguity is enhanced, contradictions and novelty, excludes as a matter of principle the introduction of the new, the unexpected and the unknown, scrupulously adhering to a consistent and obvious criterion of revisiting the past and quoting from history, without crossing the boundary of revivalism and assemblage.

It is interesting to note that all the texts on decoration are in some ways consistent with, and in some ways divergent from, the theses developed around postmodernism. Charles Jencks, for example, in his famous book The Language of Post-modern Architecture 〈19〉, curiously does not attribute any special role to decoration, although later in his discussion he constantly refers to the new importance of decoration in architecture. Such an oversight, if one can call it that, is not accidental. Postmodernism, as Jencks sees it, and as many others after him will continue to see it, is limited to an emphasis on contextualisation, nationalism, ethnic and vernacular languages, historicism, eclecticism, or what Andrea Branzi has aptly defined as the neo-academia 〈20〉. Postmodernism, although Jencks does not fail to cite Venturi’s text, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture 〈21〉, where precisely the inclusive formula of “both/and” is elaborated for the first time and the aesthetic potential of an architecture laden with ambiguities and novelty is enhanced, This is where the inclusive formula of “both/and” is elaborated for the first time and the aesthetic potential of an architecture full of ambiguities, contradictions and novelties is enhanced, excluding as a matter of principle the introduction of the new, the unexpected and the unknown, scrupulously adhering to a consistent and obvious criterion of revisiting the past and quoting from history, without crossing the border between revivalism and assemblage.

Decoration is something else. It is revivalism and the future, history and anti-history, the tranquillity of the senses and their disturbance. It is no coincidence that decoration arouses anxiety and scandal even among its own promoters, who are careful to provide all kinds of justifications for it.

Decoration, Goldin writes, «is a phenomenon together old and new» 〈22〉. It was also practiced in Occident in the past only to be repudiated as «a sub-artistic» 〈23〉. It represents «the accompaniment of the small and large occasions of ordinary life» 〈24〉 and, unlike high art, «does not exclude utility and application» 〈25〉. After all, it is a joyful art, an art of pleasure, «an invitation to a worldly or a cosmic dance» 〈26〉. Decoration has a discontinuous and fragmentary nature, adds Jeff Perrone, decontextualising the sources of quotation and presenting a profound semantic ambiguity. «Removed from its usual role, the decoration becomes both sign and design, both itself and quoted material […]» 〈27〉. John Perreault insists on its anti-sexist character, because it is so close to the manual and artisanal 〈28〉, while Richard Marshall’s inclusion of expressions of the “new image” in decoration (decoration can be indifferently abstract or figurative) simply emphasises its character as a new sensibility, an unmistakable sensibility that transcends classical notions of style, trend or group 〈29〉.

Decoration thus abolishes dichotomies, breaks down hierarchies, arranges the valences of art and non-art, the demands of novelty and tradition, the impulses of the future and the memories of the past horizontally and equally. It expresses the pleasure, the delight, the joy of art. It does not shy away from mass appreciation. Decoration hides nothing. As has been said, everything there is made to be seen, and there is nothing beyond what cannot be seen. It is an art of pure perceptual surface, of simple happenings, self-evident and manifest. Yet it has challenged many conventional ideas about art.

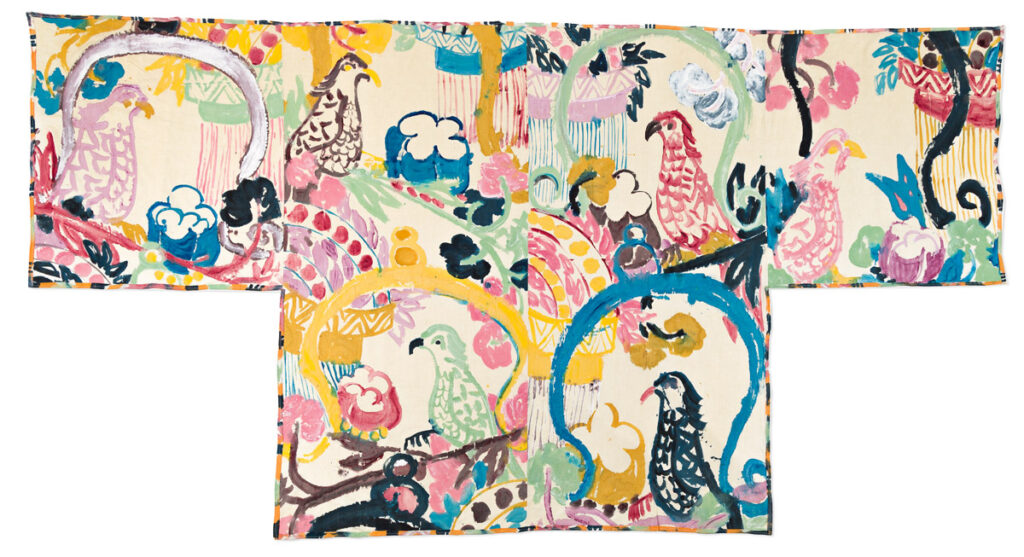

〈1〉 Quoted as a motto of the Modern Movement by R. Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, New York, 1966, p. 16. 〈2〉 T. Carlyle, Sartor Resartus: the Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books, London-New York, 1901 (original edition 1836). 〈3,4,5〉 Ibidem, pp. 33, 34, 6. 〈6〉 A. Moles, Psychologie du kitsch: l'art du bonheur, Paris, 1971. 〈7,8〉 Ibidem, pp. 7, 23. 〈9〉 M. Tucker, "Bad" Painting, exhibition catalog, New York, New Museum, january-february 1978. 〈10〉 The only professional artists in the exhibition were Neil Jenney and William Wegman, exponents of the new trends in decorative art and teh "new image". 〈11〉 R. Poggioli, Teoria dell'arte d'avanguardia, Bologna, 1962, quoted by Tucker in American edition, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, New York, 1968. 〈12〉 Ibidem, p. 81. 〈13〉 R.Musil, Über die Dummheit, Wien, 1937. 〈14,15〉 Ibidem, pp. 40, 43. 〈16〉 Exhibition held at the Venice Biennale in 1980 as part of the 1st International Architecture Exhibition. 〈17〉 A. Mendini, Elogio del banale, exhibition catalog, Turin, Studio Forma, Milan, Alchimia, 1980, p.14. 〈18〉 Ibidem. 〈19〉 Ch. Jencks, The Language of Post-Modern Architecture, New York 1977. 〈20〉 A. Branzi, Postmodernismo e/o neoaccademia, in Moderno Postmoderno Millenario, Turin, Studio Forma/Milan, Alchimia, 1980, p. 100. 〈21〉 R. Venturi, op. cit. 〈22〉 A. Goldin, introduction to exhibition catalog, Patterning & Decoration, Miami, Florida, The Museum of the American Foundation, october-november 1977, p. 3. 〈23,24,25,26〉 Ibidem. 〈27〉 J. Perrone, Approaching the Decorative, "Artforum", december 1976, p. 26. 〈28〉 J. Perreault, Issues in Pattern Painting, "Artforum", november 1977, p. 33. 〈29〉 R. Marshall, introduction to exhibition catalog, New Image Painting, New York, Whitney Museum of American Art, december 1978 - january 1979. Homepage: Andrea Branzi-Archizoom Associati, La Farfalla di Battista, linen fabric prototype, Poltronova production, 1967 (www.cambiaste.com). Below: Kendall Shaw, Sunship (for John Coltrane), 1982, mixed media on overlapping canvases, 256 x 256 x 18 cm, New Orleans, Ogden Museum of Southern Art.