by the editorial staff

In the academies of fine arts, the ornamental repertoires had their own specific disciplinary territory, ornamentation, the study of which transcended all languages, both two-dimensional, such as painting and graphics, and three-dimensional, such as sculpture, architecture and scenography. Today things are different. Artists often come across ornamental motifs by chance and reuse them in a strictly individual way, out of context. The ornament is something like an objet trouvé, an entity that is often encountered by chance. But unlike the Dadaist objet trouvé, each geometric motif is charged with resonances, symbolism and subtexts rooted in the distant past. The danger of falling into kitsch, of pandering to the stereotypes that abound on the Internet, is always present. To test today's sensitivity to these issues, we put some questions to two students of the painting courses at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, Simone Bertuzzi (Asola 2003) and Davide Infantino (Milan 1985), both of whom are engaged in the search for minimal, modulable and repeatable forms in a pictorial space that's always ready to split into real space. Their works intersect, through highly effective technical inventions, the structural and utilitarian rather than expressive aspects of decoration, reflecting its constant presence in the human environment.

What were your first significant contacts with the art world?

SB The most important were, and still are, my father, a painter and decorator, my mother, a primary school teacher, and an uncle who was a restorer for the Superintendencies for Historical and Artistic Heritage. It was from them that I received my first impulses.

DI Like many teenagers from the suburbs of Milan, my first contact with the art world coincided with the discovery of graffiti art on the walls of the city. Then I started visiting exhibitions and galleries, especially the Milan Triennale. It was here that I discovered international design and architecture, and was particularly impressed by the work of Ettore Sottsass and the Memphis Group. This communicative aesthetic (I’m thinking, for example, of Nathalie Du Pasquier’s graphic sensibility), this way of understanding design that straddles art and craftsmanship, immediately struck me. But my interests have never been sectoral, and I have also been attracted by primitive and non-European arts.

The technical processes by which your works are created have some rather unusual aspects compared to the standard brush dipped in paint. Could you tell us about them?

SB The abandonment of traditional tools is an established fact in contemporary art. It’s all about inventing the tools and materials that best suit your needs. For the kind of work I am currently doing, it became necessary to invent a ‘rake’ made from a broom handle and a toothed spatula screwed together. This allowed me to create geometric effects by working more comfortably and directly on the surfaces I was interested in.

DI Painting is one of the many aspects of my artistic practice. Through my work I do not, as is often said, aim to ‘express myself’, but rather to bring out a prior, universal idea. I prefer a strictly functional way of working that covers the whole range of my expressive interests. So when I paint on a wall, I try to work with the bare minimum. I believe that the real challenge for an artist is to measure himself against different media and to adapt his language to the environment in which he finds himself.

As a corollary to the previous question: your works give life to images that are often indirect, and seem to have matrices, moulds, geometric patterns behind them, matured in contexts other than ‘pure’ painting. Where do you get these thematic clues from? Do you rely on chance or on a strategy?

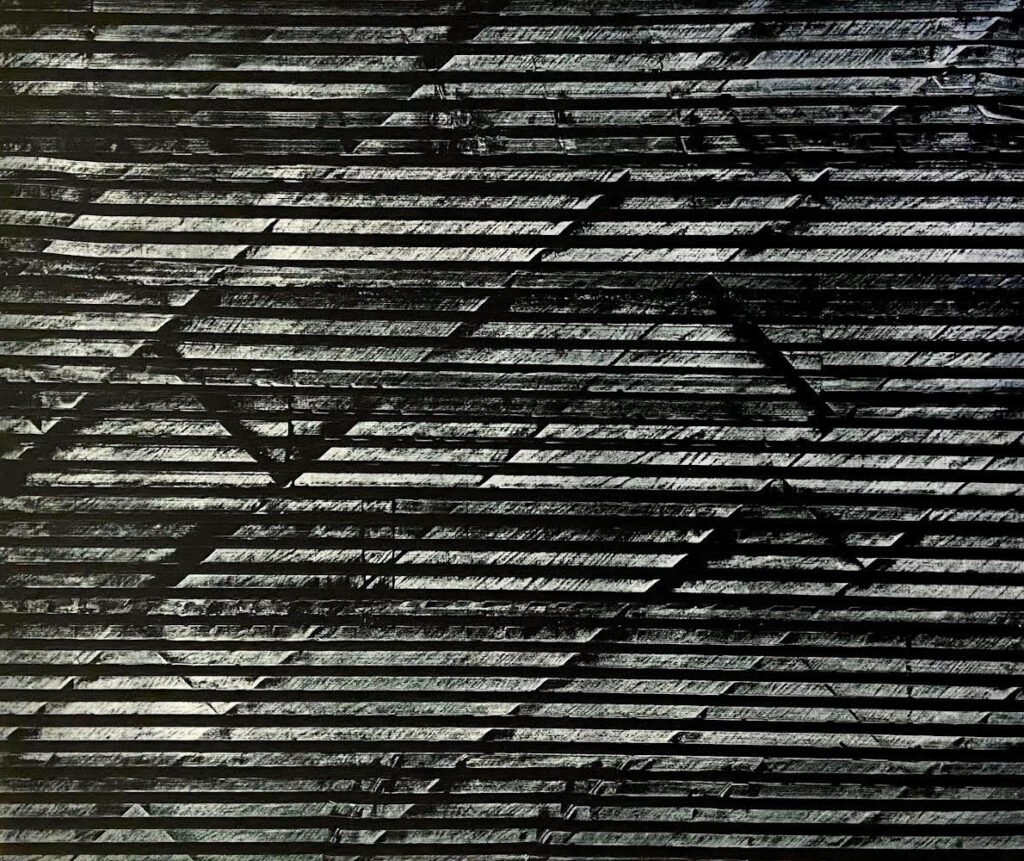

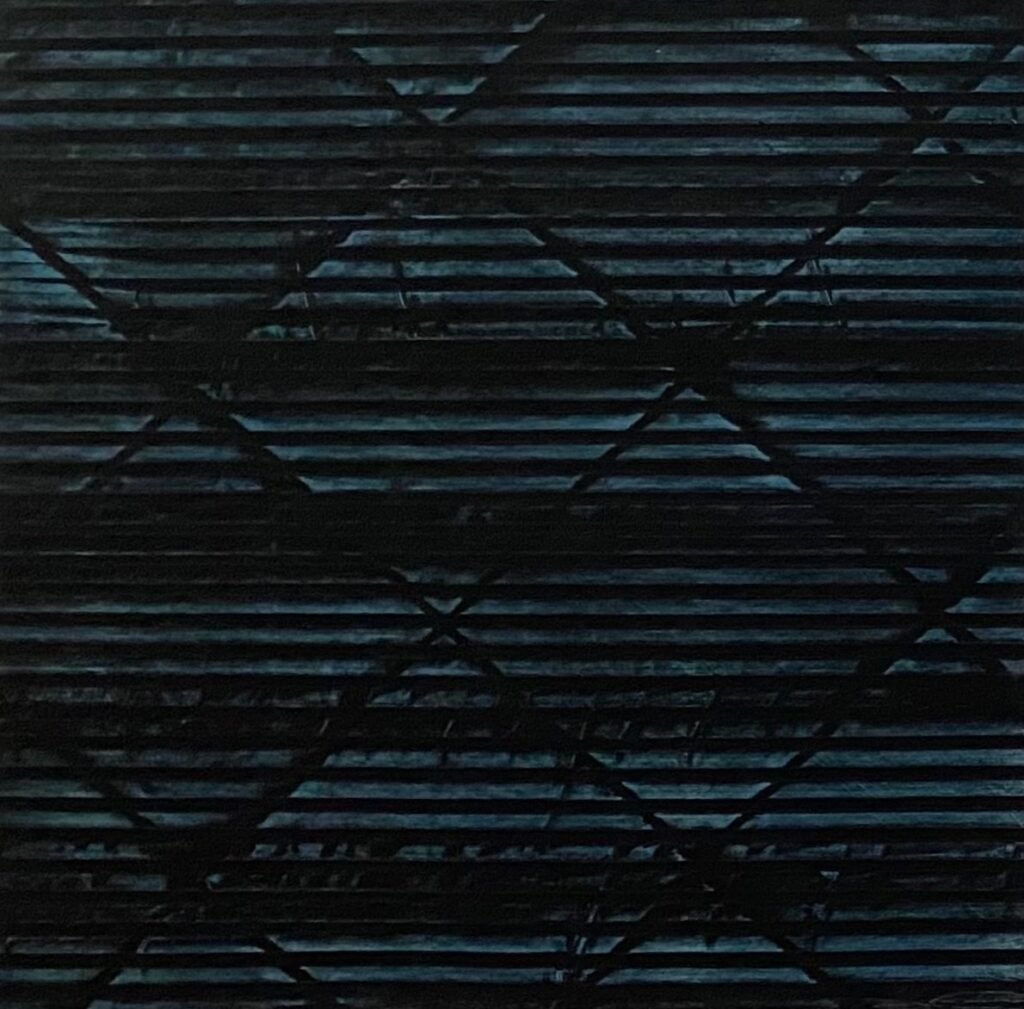

SB In the paintings of the series I am working on, nothing is left to chance; there is a technical rigour that involves many steps. First of all, patience and attention to detail are required, from the construction of the frame to the cutting of the canvas from recycled fabric. A first frame is used to prepare the canvas with Bologna chalk and vegetable glue. The canvas is then quickly removed from the frame and placed on the chosen surface. The paint is spread on the surface and the rake is passed over it to create a double geometry; the first and most visible is the mark left by the tool, while the second is brought to life by the pressure of the rake on the surface (tile or other), creating a frottage that gives depth to the painting. The last stage is the final framing and any retouching.

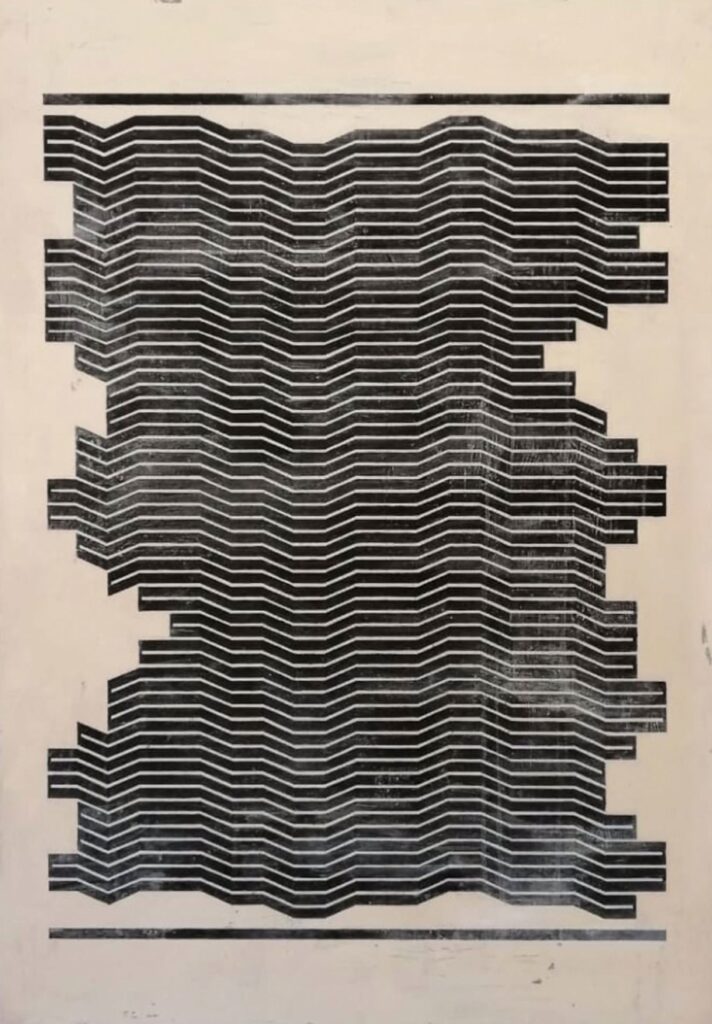

DI The reference to art history is essential for me, and initially Piet Mondrian’s reflection on the discipline of colour and line played a fundamental role. Verticals, horizontals and diagonals – seen in their reciprocal relationships – and primary colours were my guide to a possible conception of the world, with its own visual, communicative and architectural structure, as seen in the series Untitled Block-Manifesto, later taken up in a variant, Manifesto Segnico, in which the curved line, previously excluded from my practice, appears. I also attach great importance to the concept of sequence, in which ever-changing combinations of lines give rise to potentially infinite compositions, as occurs in music. In this sense, my work is closer to that of a designer than that of a painter tout court. I must admit that architecture, as an anthropological experience inherent to civilisations of all ages, has given me valuable suggestions. Suggestions from visionary writers such as Philip K. Dick, Aldous Huxley, George Orwell and H.P. Lovecraft have also had a certain influence.

In the light of what has been said so far, do you think that the Academy’s division of the visual arts into painting, sculpture, decoration and graphics is still relevant or do you think it is outdated?

SB I believe that the Academy’s division into departments is in keeping with the times. It is right to maintain a reference to tradition with the four historical courses, thus avoiding the risk of general homologation. Organised in this way, the Academy also encourages the exchange of ideas and practices between students enrolled in the different courses. The uniqueness of each course is enhanced, while at the same time creating a broad and diverse working group.

DI However, it is important for students to be able to move from one department to another, choosing freely between the teachers present, if this is useful for their artistic growth. I see the Academy as a gymnasium where you can train and make mistakes, trying to find your own way, which is not easy when it comes to creativity.

Although you are not a street artist, the dimension of the street, of urban space and its surfaces, is implicit in your work. What do you think of street art and, more generally, of so-called public art? Do you compare yourself to these realities or is it just a coincidental intervention?

SB The reference to street art in my works is coincidental; the dimension of space, with its surfaces, is present at the moment when the actual pictorial action takes place on the chosen surfaces. Surfaces that can be of different kinds, from a private place, such as the inside of a house, to the public place par excellence: the square. I seek a coherent relationship between the work and the place, a relationship that is proper to public art, but which is also a fundamental principle of decoration in all its forms.

DI As a global and diverse phenomenon, street art attracts very different audiences and artists. I find some of the movement’s exponents interesting, especially the pioneers, while aspects that do not convince me are the excessive and general political-ideological connotations of many works and the too many references to pop culture. What attracts me more are those who choose the aniconic route for a freer approach to the wall and to space; to name but a few, Roberto Ciredz and Guido Bisagni aka 108, the exponents of a kind of “contemporary muralism”. As for public art, it is perhaps the most difficult challenge for an artist. The work must not impose itself on the public, but integrate itself into the urban and social fabric that is called upon to receive it. In this sense, I believe that in recent years large-scale mural painting has met the challenge of establishing a dialogue with the space and, at the same time, with the viewer.

An obvious question, perhaps, but always appropriate: who are the artists (other than those active in the Brera Academy) who inspire you in any way and to whom you feel you owe something?

SB Artists working in the field of Optical and Minimal Art seem to me to be more relevant than ever; the two approaches often merge, resulting in highly effective operations. The simplicity and synthesis of Minimal combine perfectly with the illusionism of Optical. Bridget Riley or, in a different way, Valerie Jaudon are among my favourite examples; by managing complex linear patterns, they guide the viewer in the space they create.

DI A fundamental reference for me, besides Piet Mondrian, is certainly the work of Sol LeWitt. I would add an experience like that of Pattern and Decoration, with artists like Joyce Kozloff and Valerie Jaudon, and a master of architecture like Gio Ponti, as well as some contemporary muralists. I am interested in bringing together different influences in my work, in terms of time and origin, without identifying with any one of them.

Is there an ideal project you would like to work on?

SB I am currently in a phase in which the path to follow is not yet clear to me, also due to the large number of suggestions and experiences during the years of the academy, which make the identification of a specific path very complex. In the near future I would like to create large private and public mural works that enhance the place in which they are located.

DI Carrying out an intervention on an architectural structure, external or internal, also collaborating with expert craftsmen, to bring together tradition and contemporaneity in an all-encompassing concept. But I also like to work at minimal levels, both technically and linguistically-conceptually, using the means available to create site-specific works that are always different from time to time, in terms of creative logic and environmental context.

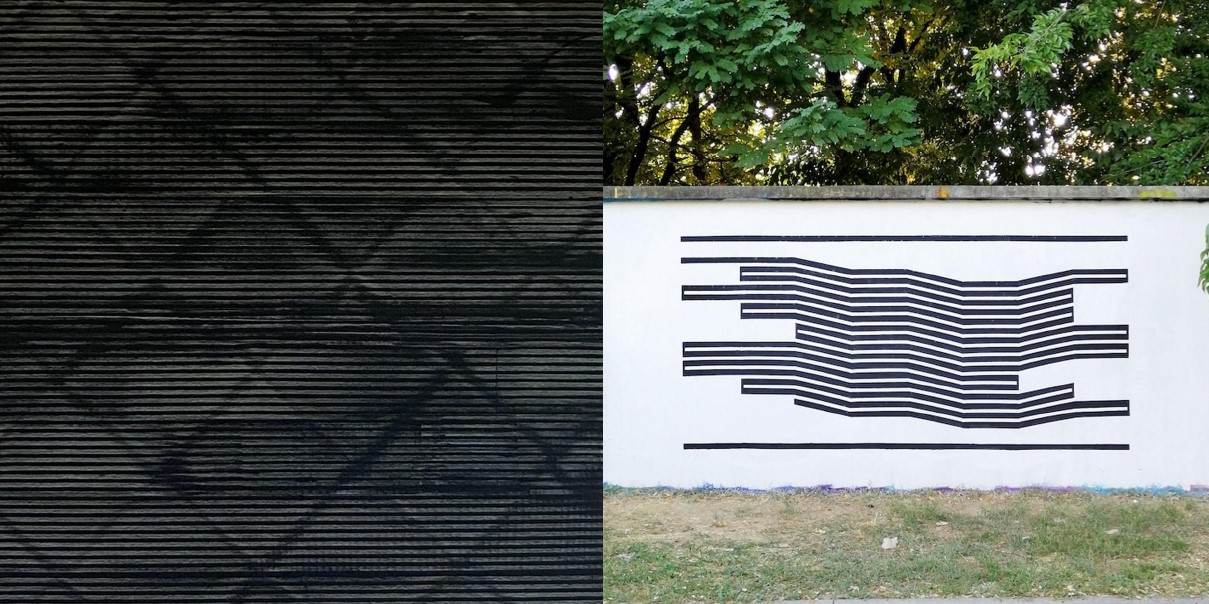

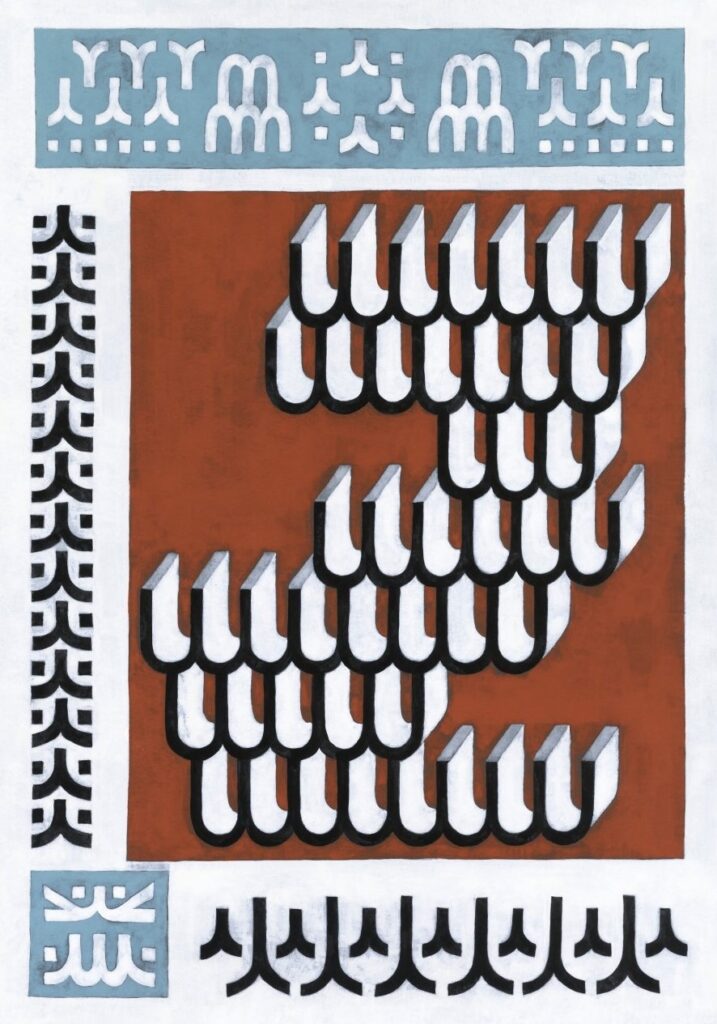

Homepage; 1) Simone Bertuzzi, Geometrie imperfette, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 150 x 150 cm 2) Davide Infantino, Wall Painting, 2021, water paint, approximately 2,5 x 4 m. Below; 1) Davide Infantino, Senza titolo, 2020, shaped cardboard, 60 x 20 cm 2) Simone Bertuzzi, Geometrie imperfette, 2023, acrylic on canvas, 120 x 140 cm (photo credits S. Bertuzzi, D. Infantino).