by Enrico Maria Davoli

The Venice Architecture Biennale, the 18th since the event’s inception in 1980, closed on 26 November with an excellent public response and much attention from the international press and media. This is good news, because the organisational effort was remarkable, and it best accompanied artistic director Lesley Lokko (Scottish-Ghanaian, professor of architecture and writer) in the realisation of her exhibition project entitled The Laboratory of the Future. It is an effective representation of Lokko’s cultural milieu and the practitioners from all over the world, but mainly from the African diaspora, whom she has invited to Venice. However, the aim was different: to take stock of the political, economic and ecological horizons that, in Lokko’s view, make the decolonisation and decarbonisation of the planet impossible to postpone.

If by diaspora one simply means the condition of so many professionals, artists and intellectuals of African descent (including Lokko) living abroad, then the Venice exhibition provided a credible cross-section of them. It is another thing, however, to understand how much the architects/artists/researchers gathered in Venice really have the pulse of their homelands, since their point of observation is mostly identified with the Western capitals where they live and work: New York, London, Paris, Berlin, Amsterdam and so on. Only a minority live and work in their home countries, and here a leading economic power such as South Africa stands out, with two “global” metropolises such as Cape Town and Johannesburg. The same has long been true of the Biennale; so many authors of African or Asian origin, and yet Americanised or Europeanised.

It should be noted that Africa (a vast continent which it is absurd to continue to treat as a whole, but the time is obviously not yet ripe) is not the only “global south” on which The Laboratory of the Future has focused. It included case studies of African-American communities in the US, the Amazonian population of Colombia, the Chinese population of Xinijang who were imprisoned and re-educated en masse by the central government, and then nomadic communities in the Maghreb and Switzerland, prehistoric settlements in Ukraine, and so many other areas in search of an acceptable transition that would remedy the failures of forced industrialisation. Many of these thematic insights have not led to architectural or urban planning proposals (however broadly this discipline is presented to the public today), but to statistical, sociological and anthropological studies, sometimes more, sometimes less interesting. The Golden Lion for Extravagance goes to an analysis of Borgo Rizza, a Sicilian village of Fascist origin that has been redeemed from its original sin (or, if you prefer, “decolonised”) by an installation performance worthy of Beckett and Ionesco’s Theatre of the Absurd.

Along the lines of the main exhibition, the national pavilions, as always, offered special and surprising scenarios to be explored one by one. Two European pavilions stand out: the Hungarian pavilion, with the new Ethnographic Museum of Budapest, and the Romanian pavilion, dedicated to the role of scientific and technological invention as an activator of interdisciplinary processes. The completely sealed Israeli pavilion, where a buzzing sound coming from inside symbolised the IT cloud enveloping the country, sounded like an uncanny omen on reflection. Not far away was the Russian pavilion, now in its third year of forced closure. Finally, the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement was awarded to Nigerian architect, designer, artist and writer Demas Nwoko (1935).

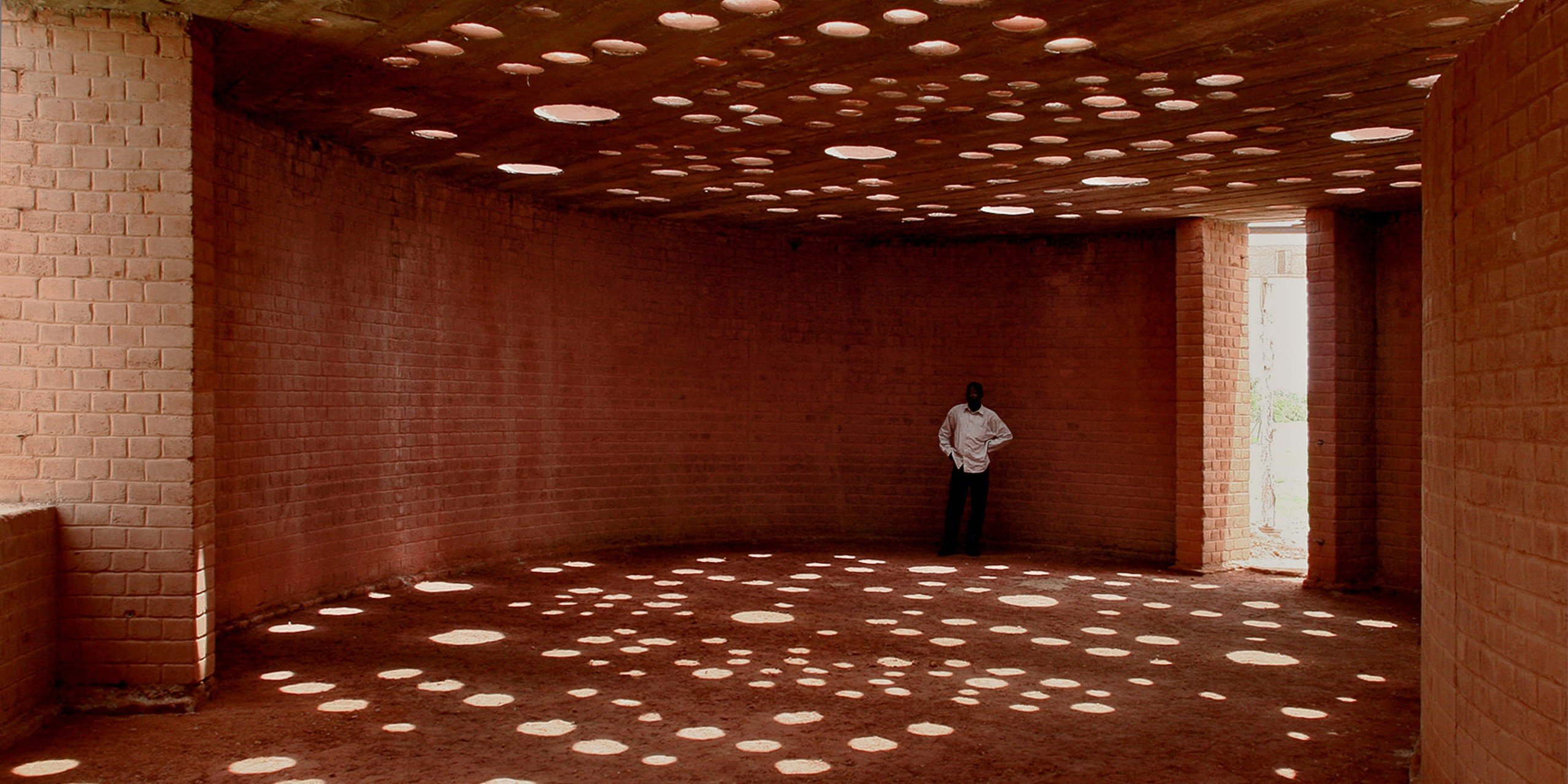

Homepage; Francis Kéré, Primary School (the architect is posing inside the library), 2001, Gando, Burkina Faso (photo credits Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk/Biennale di Venezia).

Below; Demas Nwoko, the architect's house-atelier, 1976, Idumuje Ugboko, Nigeria (www.mondafrique.com).