by Georg Simmel

Berlin-born Georg Simmel (1858-1918) is, with Émile Durkheim and Max Weber, among the founding fathers of sociology. As can be seen from his best-known essay, Philosophy of Fashion (Philosophie der Mode, 1905), he was always very attentive to artistic and cultural facts, which he considered, like political-economic facts, to be eloquent indicators of social relations and their evolution. Like other of his writings, Adornment came out in a review, later becoming part of the essay Sociology (Soziologie), published by Simmel in 1908 at the Duncker & Humblot publishing house in Leipzig. In this case, the chronological gap between the first issue and the re-edition in volume is very small: the original text, entitled Psychologie des Schmuckes, appeared in No. 15, 1908, of the weekly «Der Morgen. Wochenschrift für Deutsche Kultur», and reappears shortly afterwards, under the title Exkurs über den Schmuck, in Soziologie. Beware of the German title: the noun "schmuck" means "jewel", "necklace" and then, in a more general sense, "ornament". In this ambivalence lies the whole sense of Simmel's reflection: he in fact devotes himself to the analysis of bodily adornment (clothes, jewellery), as it pertains to the individual, while he does not consider fields such as architecture and design, as they do not apply directly to the person. From an imaginative point of view, Simmel's auratic, almost deified conception of the clothed body reflects the symbolist and expressionist climate of the time. To conclude, a remark on the year in which Simmel's text appeared: in that same 1908, and again in German, Adolf Loos's programmatic manifesto Ornament and Crime took shape in Vienna, while Wilhelm Worringer's book Abstraction and Empathy was published in Munich. The year 1908 was therefore a divide in the debate on decoration and its relationship with the arts, inaugurating a theoretical perspective that, between iconoclasm and rehabilitation, still persists today. The English edition quoted here: K. H. Wolff (ed.), The Sociology of Georg Simmel, The Free Press, Glencoe, Illinois 1950, pp. 338-344. Images accompanying the text are an editorial choice.

Man’s desire to please his social environment contains two contradictory tendencies, in whose play and counterplay in general, the relations among individuals take their course. On the one hand, it contains kindness, a desire of the individual to give the other joy; but on the other hand, there is the wish for this joy and these “favors” to flow back to him, in the form of recognition and esteem, so that they be attributed to his personality as values. Indeed, this second need is so intensified that it militates against the altruism of wishing to please: by means of this pleasing, the individual desires to distinguish himself before others, and to be the object of an attention that others do not receive. This may even lead him to the point of wanting to be envied. Pleasing may thus become a means of the will to power: some individuals exhibit the strange contradiction that they need those above whom they elevate themselves by life and deed, for they build their own self-feeling upon the subordinates’ realization that they are subordinate.

The meaning of adornment finds expression in peculiar elaborations of these motives, in which the external and internal aspects of their forms are interwoven. This meaning is to single the personality out, to emphasize it as outstanding in some sense – but not by means of power manifestations, not by anything that externally compels the other, but only through the pleasure which is engendered in him and which, therefore, still has some voluntary element in it. One adorns oneself for oneself, but can do so only by adornment for others. It is one of the strangest sociological combinations that an act, which exclusively serves the emphasis and increased significance of the actor, nevertheless attains this goal just as exclusively in the pleasure, in the visual delight it offers to others, and in their gratitude. For, even the envy of adornment only indicates the desire of the envious person to win like recognition and admiration for himself; his envy proves how much he believes these values to be connected with the adornment. Adornment is the egoistic element as such: it singles out its wearer, whose self-feeling it embodies and increases at the cost of others (for, the same adornment of all would no longer adorn the individual). But, at the same time, adornment is altruistic: its pleasure is designed for the others, since its owner can enjoy it only insofar as he mirrors himself in them; he renders the adornment valuable only through the reflection of this gift of his. Everywhere, aesthetic formation reveals that life orientations, which reality juxtaposes as mutually alien, or even pits against one another as hostile, are, in fact, intimately interrelated. In the same way, the aesthetic phenomenon of adornment indicates a point within sociological interaction – the arena of man’s being-for-himself and beingfor-the-other – where these two opposite directions are mutually dependent as ends and means.

Adornment intensifies or enlarges the impression of the personality by operating as a sort of radiation emanating from it. For this reason, its materials have always been shining metals and precious stones. They are “adornment” in a narrower sense than dress and coiffure, although these, too, “adorn.” One may speak of human radioactivity in the sense that every individual is surrounded by a larger or smaller sphere of significance radiating from him; and everybody else, who deals with him, is immersed in this sphere. It is an inextricable mixture of physiological and psychic elements: the sensuously observable influences which issue from an individual in the direction of his environment also are, in some fashion, the vehicles of a spiritual fulguration. They operate as the symbols of such a fulguration even where, in actuality, they are only external, where no suggestive power or significance of the personality flows through them. The radiations of adornment, the sensuous attention it provokes, supply the personality with such an enlargement or intensification of its sphere: the personality, so to speak, is more when it is adorned.

Inasmuch as adornment usually is also an object of considerable value, it is a synthesis of the individual’s having and being; it thus transforms mere possession into the sensuous and emphatic perceivability of the individual himself. This is not true of ordinary dress which, neither in respect of having nor of being, strikes one as an individual particularity; only the fancy dress, and above all, jewels, which gather the personality’s value and significance of radiation as if in a focal point, allow the mere having of the person to become a visible quality of its being. And this is so, not although adornment is something “superfluous,” but precisely because it is. The necessary is much more closely connected with the individual; it surrounds his existence with a narrower periphery. The superfluous “flows over,” that is, it flows to points which are far removed from its origin but to which it still remains tied: around the precinct of mere necessity, it lays a vaster precinct which, in principle, is limitless. According to its very idea, the superfluous contains no measure. The free and princely character of our being increases in the measure in which we add superfluousness to our having, since no extant structure, such as is laid down by necessity, imposes any limiting norm upon it.

This very accentuation of the personality, however, is achieved by means of an impersonal trait. Everything that “adorns” man can be ordered along a scale in terms of its closeness to the physical body. The “closest” adornment is typical of nature peoples: tattooing. The opposite extreme is represented by metal and stone adornments, which are entirely unindividual and can be put on by everybody. Between these two stands dress, which is not so inexchangeable and personal as tattooing, but neither so un-individual and separable as jewelry, whose very elegance lies in its impersonality. That this nature of stone and metal – solidly closed within itself, in no way alluding to any individuality; hard, unmodifiable – is yet forced to serve the person, this is its subtlest fascination. What is really elegant avoids pointing to the specifically individual; it always lays a more general, stylized, almost abstract sphere around man – which, of course, prevents no finesse from connecting the general with the personality. That new clothes are particularly elegant is due to their being still “stiff”; they have not yet adjusted to the modifications of the individual body as fully as older clothes have, which have been worn, and are pulled and pinched by the peculiar movements of their wearer – thus completely revealing his particularity. This “newness,” this lack of modification by individuality, is typical in the highest measure of metal jewelry: it is always new; in untouchable coolness, it stands above the singularity and destiny of its wearer. This is not true of dress. A long-worn piece of clothing almost grows to the body; it has an intimacy that militates against the very nature of elegance, which is something for the “others,” a social notion deriving its value from general respect.

If jewelry thus is designed to enlarge the individual by adding something super-individual which goes out to all and is noted and appreciated by all, it must, beyond any effect that its material itsfclf may have, possess style. Style is always something general. It brings the contents of personal life and activity into a form shared by many and accessible to many. In the case of a work of art, we are the less interested in its style, the greater the personal uniqueness and the subjective life expressed in it. For, it is with these that it appeals to the spectator’s personal core, too – of the spectator who, so to speak, is alone in the whole world with this work of art. But of what we call handicraft – which because of its utilitarian purpose appeals to a diversity of men – we request a more general and typical articulation. We expect not only that an individuality with its uniqueness be voiced in it, but a broad, historical or social orientation and temper, which make it possible for handicraft to be incorporated into the life-systems of a great many different individuals. It is the greatest mistake to think that, because it always functions as the adornment of an individual, adornment must be an individual work of art. Quite the contrary: because it is to serve the individual, it may not itself be of an individual nature – aslittle as the piece of furniture on which we sit, or the eating utensil which we manipulate, may be individual works of art. The work of art cannot, in principle, be incorporated into another life – it is a self-sufficient world. By contrast, all that occupies the larger sphere around the life of the individual, must surround it as if in ever wider concentric spheres that lead back to the individual or originate from him. The essence of stylization is precisely this dilution of individual poignancy, this generalization beyond the uniqueness of the personality – which, nevertheless, in its capacity of base or circle of radiation, carries or absorbs the individuality as if in a broadly flowing river. For this reason, adornment has always instinctively been shaped in a relatively severe style.

Besides its formal stylization, the material means of its social purpose is its brilliance. By virtue of this brilliance, its wearer appears as the center of a circle of radiation in which every closeby person, every seeing eye, is caught. As the flash of the precious stone seems to be directed at the other – like the lightning of the glance the eye addresses to him – it carries the social meaning of jewels, the being-for-the-other, which returns to the subject as the enlargement of his own sphere of significance. The radii of this sphere mark the distance which jewelry creates between men – “I have something which you do not have.” But, on the other hand, these radii not only let the other participate: they shine in his direction; in fact, they exist only for his sake. By virtue of their material, jewels signify, in one and the same act, an increase in distance and a favor.

For this reason, they are of such particular service to vanity – which needs others in order to despise them. This suggests the profound difference which exists between vanity and haughty pride: pride, whose self-consciousness really rests only upon itself, ordinarily disdains “adornment” in every sense of the word. A word must also be added here, to the same effect, on the significance of “genuine” material. The attraction of the “genuine,” in all contexts, consists in its being more than its immediate appearance, which it shares with its imitation. Unlike its falsification, it is not something isolated; it has its roots in a soil that lies beyond its mere appearance, while the unauthentic is only what it can be taken for at the moment. The”genuine” individual, thus, is the person on whom one can rely even when he is out of one’s sight. In the case of jewelry, this more-than-appearance is its value, which cannot be guessed by being looked at, but is something that, in contrast to skilled forgery, is added to the appearance. By virtue of the fact that this value can always be realized, that it is recognized by all, that it possesses a relative timelessness, jewelry becomes part of a super-contingent, super-personal value structure. Talmi-gold and similar trinkets are identical with what they momentarily do for their wearer; genuine jewels are a value that goes beyond this; they have their roots in the value ideas of the whole social circle and are ramified through all of it. Thus, the charm and the accent they give the individual who wears them, feed on this super-individual soil. Their genuineness makes their aesthetic value – which, too, is here a value “for the others” – a symbol of general esteem, and of membership in the total social value system.

There once existed a decree in medieval France which prohibited all persons below a certain rank to wear gold ornaments. The combination which characterizes the whole nature of adornment unmistakably lives in this decree: in adornment, the sociological and Aesthetic emphasis upon the personality fuses as if in a focus; being-for-oneself and being-for-others become reciprocal cause and effect in it. Aesthetic excellence and the right to charm and please, are allowed, in this decree, to go only to a point fixed by the individual’s social sphere of significance. It is precisely in this fashion that one adds, to the charm which adornment gives one’s whole appearance, the sociological charm of being, by virtue of adornment, a representative of one’s group, with whose whole significance one is “adorned.” It is as if the significance of his status, symbolized by jewels, returned to the individual on the very beams which originate in him and enlarge his sphere of impact. Adornment, thus, appears as the means by which his social power or dignity is transformed into visible, personal excellence.

Centripetal and centrifugal tendencies, finally, appear to be fused in adornment in a specific form, in the following information. Among nature peoples, it is reported, women’s private property generally develops later than that of men and, originally, and often exclusively, refers to adornment. By contrast, the personal property of the male usually begins with weapons. This reveals his active and more aggressive nature: the male enlarges his personality sphere without waiting for the will of others. In the case of the more passive female nature, this result – although formally the same in spite of all external differences – depends more on the others’ good will. Every property is an extension of personality; property is that which obeys our wills, that in which our egos express, and externally realize, themselves. This expression occurs, earliest and most completely, in regard to our body, which thus is our first and most unconditional possession. In the adorned body, we possess more; if we have the adorned body at our disposal, we are masters over more and nobler things, so to speak. It is, therefore, deeply significant that bodily adornment becomes private property above all: It expands the ego and enlarges the sphere around us which is filled with our personality and which consists in the pleasure and the attention of our environment. This environment looks with much less attention at the unadorned (and thus as if less “expanded”) individual, and passes by without including him. The fundamental principle of adornment is once more revealed in the fact that, under primitive conditions, the most outstanding possession of women became that which, according to its very idea, exists only for others, and which can intensify the value and significance of its wearer only through the recognition that flows back to her from these others. In an aesthetic form, adornment creates a highly specific synthesis of the great convergent and divergent forces of the individual and society, namely, the elevation of the ego through existing for others, and the elevation of existing for others through the emphasis and extension of the ego. This aesthetic form itself stands above the contrasts between individual human strivings. They find, in adornment, not only the possibility of undisturbed simultaneous existence, but the possibility of a reciprocal organization that, as anticipation and pledge of their deeper metaphysical unity, transcends the disharmony of their appearance.

Homepage; Georg Simmel in an anonymous photo circa 1914 (Wikimedia/Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz).

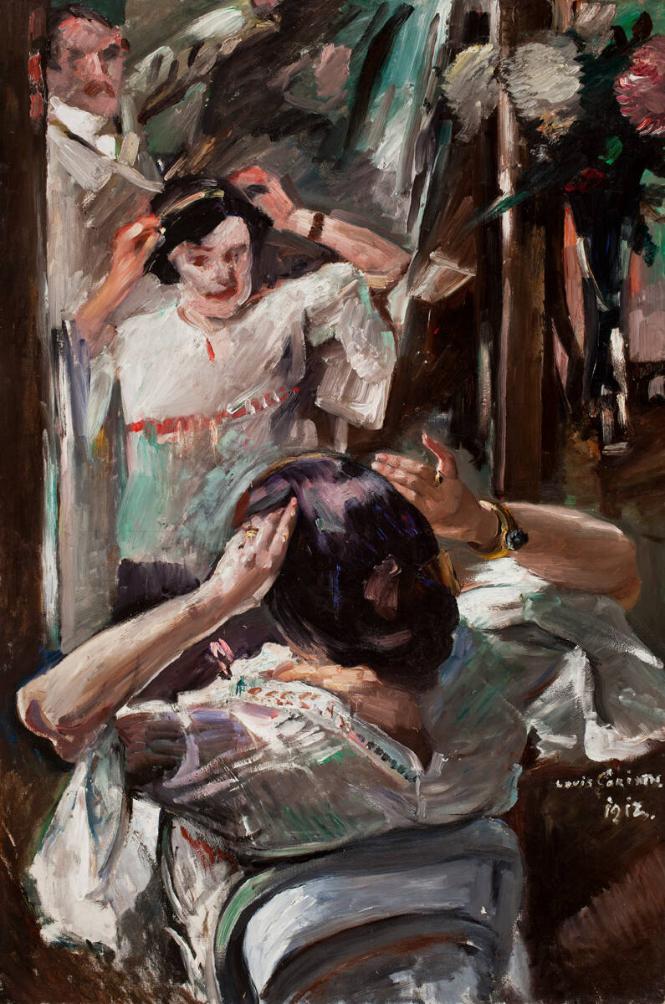

Below; Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Rose von Rosthorn-Friedmann, 1900-1901, oil on canvas, 140 x 80 cm, Private Collection (Wikimedia).